Nearly 50 billion coconuts are grown worldwide each year and 85% of these coconuts’ husks (outer shells) are wasted. Coconut water is also often found as a waste product after coconut flesh is harvested. This wasted coconut water often gets discharged into the drainage system but coconut water spoils easily, causing pollution in rivers and streams and soils to become acidified.

Coconuts are a big part of South Indian cuisine because of their versatility, creaminess, and flavor. So it’s no surprise that India is the third largest coconut producer in the world, with South India home to around 90% of production in the country. The leading state of coconut cultivation is Kerala, which literally translates to ‘the land of coconuts’.

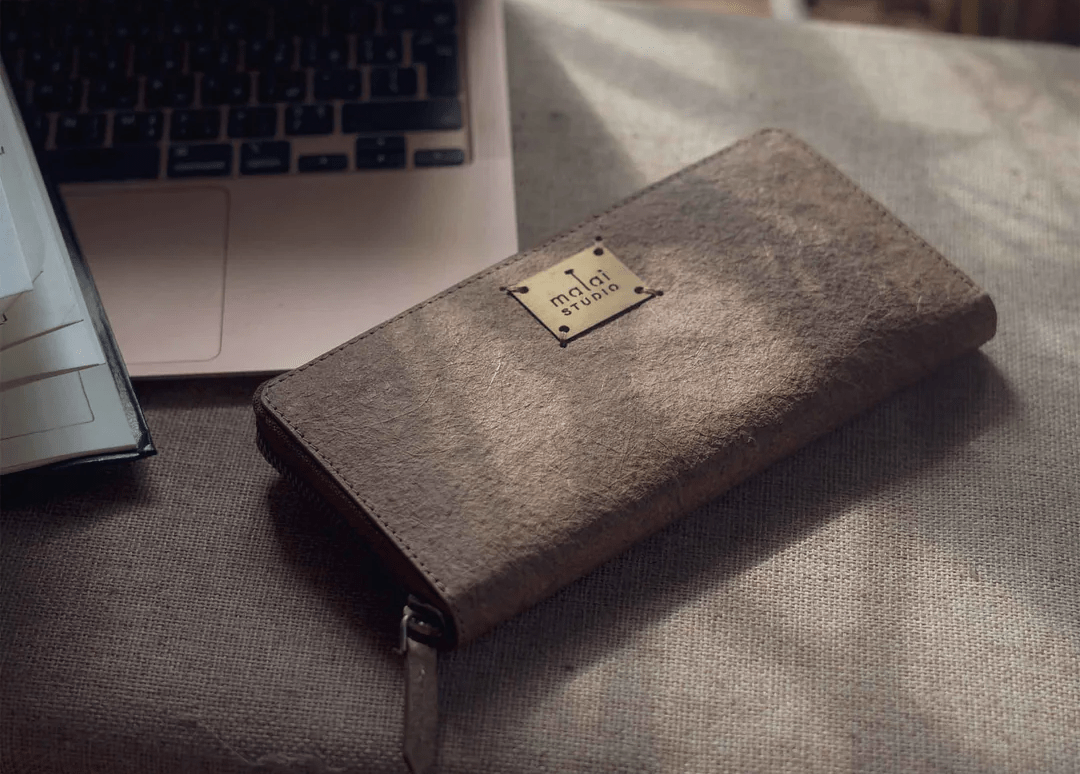

This land is where Malai was born. Malai work with South Indian coconut farmers who often find themselves with waste coconut water. They rescue and process this water into bacterial cellulose, which is used to create a new material. It’s flexible, durable, water-resistant, non-allergenic, vegan, and comparable to leather or paper.

Read on as we speak with Zuzana Gombosova, co-founder and director of Malai.

You’ve been working in material design for at least 10 years. Have you always wanted to design a sustainable material?

I didn’t know from the beginning. My background is in textiles and apparel design, so I think I’ve always had a very strong connection with materials. I’ve always been very interested in materiality and in transforming and making materials.

When I started working in the field, I realized how much textiles contribute to all sorts of health conditions. People who were working in the storage room, the people who were cutting the fabric, the tailors. I even got really bad eczema at the time. A lot of synthetic materials were around, a lot of polyesters, but maybe even the cotton fibers – they have so many treatments to make them more resilient, durable, and resistant to moisture or microbes.

Then, I was looking at where to move my practice towards. I read an article in a science publication saying that we’ve explored a lot more of outer space than we have our own microbiome on this Earth. Because if you zoom in, there’s so much left unexplored.

I started looking into microbiology a little more, and it became incredibly fascinating. You have a microbe for any metabolic function. It’s this wonderful ecosystem that works together. It’s invisible, and we rely on it in so many different ways without actually being aware of it.

So that was a starting point. I started working with a microbiologist in a lab, with different kinds of microbes, and a lot of it was really frustrating because you really don’t see anything. I got very interesting results with bacterial cellulose. So I decided to stick with it as a vehicle to explore this area of intersection of design-making and microbiology.

Producing a leather-like material actually wasn’t the intention when experimenting with coconut waste, right?

No, not at all. I mean, everybody knew, bacterial cellulose = a kind of leather. But I thought there was something much more interesting about it. You’re able to examine this almost miracle process. You’re able to grow it on many different types of agricultural waste. It has this unique microstructure. It’s actually composed of nano-sized fibers of cellulose. But because the bacteria is so tiny in size, it also produces fibers of cellulose that are nano-sized. And this gives them extremely interesting properties because they suddenly have a lot of surface area. As opposed to ordinary cellulose, which is more macroscale, bacterial cellulose gives you a material that is surprisingly strong for being made of cellulose as a funding block. You’re able to alter the material in many interesting ways because it can act as a scaffolding that you can load with a lot of active compounds so that you can engineer your material according to what it needs to do. So from the perspective of material engineering, it’s also an incredibly versatile material to work with.

Were you hoping for another kind of material?

We were initially hoping to bring some interesting material for packaging, but we weren’t able to justify the cost. So we ended up with leather because we were able to fit within that range of prices.

How do biodegradable leather and genuine leather compare, and how can we get people to shift their mindsets towards the plant-based alternative?

We tend to look at animal leather as this solution for everything because it’s so durable. Yes, if you use it and it’s good leather, it will last you easily for decades. You can rely on this material, but there’s a certain cost. And perhaps it shouldn’t be like that. We just want this solution for everything and we ended up choosing either leather or PU leather. But there are lots of applications where you don’t need the durability of 20 – 30 years.

We can work successfully with all sorts of accessories or interior products, no problem. But when it comes to applications such as automotive or footwear, it’s a lot more difficult. As a compostable, natural product, we would have to introduce either some kind of binders or crosslinkers – you have to make that compromise. I’m not entirely against the elimination of animal leather. There will be applications where the use of animal leather is completely justified – where you need to 100% rely on material strength, durability, and elasticity, and it’s hard to beat leather in it, but I don’t think your tote bag is one of those.

It’s ironic because the discourse on sustainability is all about longer-lasting products, but we wear clothes on average just 7 times. We don’t want to wear something for 20 – 30 years. In that way, your products are perfect.

Exactly, they are. And you also have to think about the people who make them. We’re obsessed with this idea of manufacturing without people. But there is an increasing number of people, and these people need to do something. There are so many communities, especially if you live in a place like Southeast Asia where people need jobs and have amazing skills. Yet all that we look at is, “Oh, can this be made cheaper?”

The fact that you can buy something made by a person from a community, where this particular skill can help them sustain, let’s say, a whole family – that’s amazing. Why don’t we value that? And I don’t blame the customers or the consumers necessarily, because there’s so much heavy marketing involved, that it’s hard to see through it.

Why do you think South India struggles with waste through coconut production, despite the fact that every part of the coconut is valued so much in this part of India and used for all kinds of purposes?

There are several reasons. For the water part that we work with, it has very low to no economic value for them. They don’t use coconut water as a drink because people prefer the taste of tender coconut water. Coconut vinegar is sometimes made, but it’s hard to sell it in India. It’s more expensive and the consumer base here is very cost-conscious so they prefer the cheaper versions of vinegar.

When it comes to things like nata de coco or bacterial cellulose, I hope this will develop over time, but up until now, producers in India have not converted their water into nata de coco. Because here in India, no one eats nata de coco, whereas in Thailand, Vietnam, China, and Indonesia, it is a popular dessert. So there’s a market for it.

We’re seeing heaps of hopeful material innovations to help fashion become more sustainable, just like Malai. What are the bumps on the road to upscaling production so that these better materials can become widespread?

There’s a lot more collaboration necessary. You have a lot of people sitting in their chairs talking about change, not actually initiating it. And very often, they are sitting in some legislative posts. Unless we change that, it’s very difficult to change the system.

Just look at funding – what do we have as funding? At least in Europe, you have Horizon 2020 and whatnot, but in most other parts of the world, you have to, as a startup, rely on venture capital funds. It’s not an easy environment to navigate, and in spite of the fact that we have all these wonderful materials and sustainable innovations, we are forced to work within timelines to return to investment in unrealistic times. So we have a sustainable product, but we do business as usual. It doesn’t meet.

There’s a lot more innovation that needs to be done in the space of business, in the way we fund projects, in the way we design the timelines for development, and think about the returns. Giving value to more than just the financial gains that the project is creating, and that’s not a job for one startup – that needs a whole society.

That’s why I’m saying I don’t mind being small. I’m just a person, you know.

What past collaboration stands out the most to you and why?

Many collaborations transformed either the brand or me as a material maker and researcher. Before we launched the product in 2018 at Prague Design Week, we asked different designers from Czech Republic and Slovakia, mostly, to use the material and make a product with their skill set. It was amazing because at the time we were still very fresh and didn’t know where exactly this material fits. People also didn’t have that much of a prejudice towards leather-alternative materials, so there were many outcomes that were genuinely refreshing. That helped us learn a lot about the material in terms of its limits and advantages.

It’s always lovely to collaborate with people who look at the material differently. Regular manufacturers are used to leather, and usually their approach is treating the material exactly like leather. Whereas if you work with a person with a more artisanal background, they try to build a relationship with a new material as opposed to force-fit it in a certain application. That’s exactly where all those years of experience and tacit knowledge come into place, and you can help bring an innovation to life.

View this post on Instagram

Do you have any new products in the pipeline that you’d like to tell us about?

Yeah, actually, we do. There’s a group of people who would have preferred a smoother material that would be suitable for things like apparel. So I went back to the starting point.

We should be launching a new material range soon. I don’t know when exactly, but probably in a couple of months. It’s a material called Malai Pure, which is a sheet of bacterial cellulose. It’s dyed using natural dyes, treated with natural oils, and it can be embossed. It looks a little closer to leather – it’s smoother and thinner. And it will have applications also in apparel.

This is a starting point. Further in the research, I would like to look at the more functional material. I would like to have a look further into cosmetological textiles. There’s a tradition in Ayurveda that touches upon the subject. Ayurvastra is basically a tradition of dyeing textiles using ayurvedic concoctions, so they have a health benefit for your skin and your microbiome.

Where would you like Malai to be a year from now?

I would like us to be a little more stable because we still depend a lot on our incoming sales. I hope that we’ll have more clients that are within our ecosystems and we can support each other a little more.

Apart from that, there are a lot of technical developments I’d like us to have within that one year, but I think I’d also like us to be a synonym for positive materials. So that we get out a little more from that bracket of vegan leather and that we are associated with materials for wellness, as well.

Sustainability can be a tricky concept to define. What’s your definition?

That’s a hard one. Sustainability is about sustaining – but you should be able to sustain only the positive things about your business. Very often, we try to sustain practices, materials, and products that actually should not be sustainable. And so it does require a very hard self-critique sometimes.

But for me, I think within our understanding, it is the ability to sustain, but sustain positive aspects. It’s about keeping yourself in check constantly. So that you don’t end up doing something just for the sake of doing it. Then, it’s troublesome.

Keen on learning more about Malai? Head over to their website for more information.

Leave a Reply