You’d think we’d call time on Fast Fashion at some point. The clothes may be cheap but they don’t last. They don’t fit well. Their designs are too trendy, so they go out of fashion. A garment that looked nice on a rack is unrecognizable after a few washes. The fabrics aren’t pleasant to touch and they rapidly decline. Wearing virgin polyester is like wearing petrol.

We could continue but it’s not because we’re elitist fashion snobs with a preference for Haute Couture; rather there’s the notorious impact on the planet and its people to consider. Fast fashion is the main reason for the fashion industry releasing an estimated 10% of global carbon emissions. Not to mention the horrible conditions workers have to endure.

Nevertheless, despite the dubious garments and the devastating effects of the industry, it seems that people can’t get enough Fast Fashion. Sales keep rising and sadly so do the side effects.

Improving the picture starts with awareness, so let’s take a look at the negative impacts of Fast Fashion across four key areas. Click on one of the links below to immediately teleport to a facts-boutique of your choice.

We’ve even included a fancy calculation about how big the world’s pile of fashion waste would rise, if it were a mountain.

- Facts on the scale of the problem

- Facts on the impact on planet

- Facts on the impact on people

- Facts on circularity & recycling

- How big is Mt. Trendy?

⛰️ The scale & backdrop

Where did ‘fast fashion’ come from? Well, the term was first coined by The New York Times in 1989 in response to Zara’s – at that point – exceptional ability to take clothes from the design stage to store racks in as little as 15 days. (New York Times, 1989).

Fast fashion isn’t slowing down, it’s accelerating. The industry is now worth around 161 billion, will reach 172 billion in 2026, and is projected to reach $220 billion by 2030. The impacts are only going to get worse, unless we change course. (The Business Research Company, 2026).

The fashion industry is responsible for 92 million tonnes of waste annually – a figure that is projected to rise to 134 million tonnes by 2030. (UNEP, 2025).

That last figure might be an underestimate. More recent reports suggest that textile waste has already hit 120million metric tonnes. (Boston Consulting Group, 2025).

Akepa is based in Barcelona, Spain, and Spain is also where you’ll find the worst fast fashion habit on the planet – dedicating a staggering 91.5% of its 30 billion yearly clothing budget to fast fashion. Europe dominates the fast fashion landscape and the second most afflicted country is the United Kingdom, with 88.5%. (Kaiia, 2025).

Global fiber production shot-up from 125 million tonnes in 2023 to 132 million tonnes in 2024. Production has more than doubled since 2000 and increased by roughly 34 million tonnes since the Paris Agreement in 2015, when the world’s nations committed to keeping global temperature rises below 2°C (and ideally below 1.5°C). (Textile Exchange, 2025).

If we assume an 800m width, and 400m radius, this 120 million tonne mountain of waste would be one of the planet’s highest mountains at 18,074 feet. It would exceed Europe’s highest mountain, Mont Blanc, by over a km. (Akepa, 2025 – see methodology at the end of the post).

🌍 Wear & tear on the planet

The fashion industry is responsible for 10% of global carbon emissions annually. This total is more than the emissions from international flights and maritime shipping combined – and far more than data centres or AI. At the current rate of growth, fashion’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are projected to increase by over 50% by 2030. (UNEP, 2025).

Emissions are going up. The latest figures from 2023-24 revealed that the apparel sector’s emissions rose by a massive 7.5%, annually, with a lot of responsibility lying with fast fashion and its reliance on virgin polyester. (Apparel Impact, 2025).

If our collective-closet were a country, it would be the world’s third largest emitter of GHGs, beneath the United States (11.1%) and above India (8.2%). (European Commission, 2025).

The fashion industry is responsible for approximately 20% of global industrial wastewater, mainly from the dyeing process, making it the second-largest water polluter globally. However, this oft-repeated stat is from before ultra-fast fashion really took off – as far back as 1999 – and hasn’t been studied authoritatively since. This means water pollution may now be even worse (European Parliament, 2020).

The fashion industry consumes 215 trillion liters (215 billion cubic meters) of water annually. This is equivalent to 86 million Olympic-sized swimming pools. (Quantis, 2018).

Despite a pledge to reach net zero by 2050 (now banned in Germany), ‘ultra-fast-fashion’ brand Shein’s emissions rose by over 170% over a two-year period. The brand now produces as much annual pollution as the entire country of Lebanon, driven largely by its reliance on air freight to ship individual packages globally. (Fossil Free Fashion Scorecard, 2025).

The cheap synthetic textiles favoured by fast fashion (like polyester and nylon) have become the 4th largest source of primary microplastics in the world’s oceans, accounting for 8% of the total. The share of synthetic fibers in clothing has ballooned from just 3% in 1960 to 68% today, making the shedding of these fibers during washing an escalating crisis. (UNEP, 2025).

Out of the planet’s 200 largest fashion brands – including many classed as fast fashion or ultra fast fashion – 55% of brands have SBTi-verified targets but fewer than a third of brands, a mere 29%, show any evidence of cutting emissions. Even fewer – only 6% – publicly reveal that they are helping their suppliers pay for the new equipment needed to stop burning fossil fuels – despite 96% of emissions being concentrated in Scope 3. (Fashion Revolution, 2025).

🧿 Bad influence & human cost

On 24 April 2013, the Rana Plaza building in Savar, Bangladesh crashed down, killing 1,134 people. The building had housed five garment factories and its collapse is the worst garment-worker disaster in history. This should have been a wake-up call and a turning point for better conditions but, since then, textile production has intensified in Bangladesh and risky worker conditions continue. (BBC, 2013).

Behind low prices are even lower wages. The average monthly wage of garment workers in the low-income countries where garment making is outsourced to, is often under $200 per month. In some countries like Bangladesh, which now accounts for about 7% of global textile production, it’s as low as $140 per month. (Statista, 2025 – via the US International Trade Commission).

A comprehensive 2025 audit of global fashion brands found that 213 out of 219 major fashion companies (97%) still cannot demonstrate that they pay a living wage to the workers in their supply chain. Despite years of repeated sustainability pledges, the vast majority of workers in key production hubs (like Bangladesh and Vietnam) earn on average 45% less than what is required to cover basic family needs. (BSBI, 2025)

The next stat highlights a psychological and financial sh*tstorm where fast fashion’s low initial price point, combined with friction-less financing, is driving young folk into spirals of debt. In 2025, 55% of Gen Z consumers admitted to using “Buy Now, Pay Later” (BNPL) services to buy clothes they could not actually afford. Then, 41% of all BNPL users missed a payment in the last year, with fashion and clothing remaining the #1 category for these financed purchases (accounting for ~41% of all BNPL transactions). (Motley Fool, 2025).

Buyers from Gen Z, born between 1997 and 2012, exhibit a clear gap between their values and behaviour. In a recent study, 94% of respondents said they support sustainable clothing but 62% bought fast fashion every month. Only 10% claimed to never purchase fast fashion. Looking at genders, women were more likely than men to advocate for sustainable clothing but less likely than them to actually buy it. (SHU, 2022)

♺ A massive circularity shortfall

Fast fashion items are only worn an estimated 7-10 times before being discarded. (Ellen Macarthur Foundation, 2017).

Recycling clothes is profoundly tricky. Because of complexities like mixed materials within clothes, less than 1% of all textiles are recycled globally (European Parliament, 2025).

Don’t believe everything you read. A study from the Changing Markets Foundation examined the green claims by fast fashion brands, including circularity and recycling. Shockingly, 59% of them didn’t hold up to scrutiny and in some cases, such as H&M, the deception rate reached 96%. (Changing Markets Foundation, 2021).

Recycled polyester may be a false solution that risks worsening pollution. 98% of the recycled polyester that’s favoured by ‘transitioning’ fast-fashion brands but also sustainable brands, like Patagonia, is made from plastic bottles – not textile waste. The consequence is that recycled synthetics end up polluting the environment with microplastics when they’re washed. (Changing Markets Foundation, 2025).

With a move towards a circular textile economy, the fashion industry could see waste recycling rates surpass 30%. The benefits could be huge – generating fibers worth more than $50 billion and creating around 180,000 new jobs. (Boston Consulting Group, 2025).

There are some solutions that could shift mindsets. According to a 2025 study, labelling clothes with a Cost Per Wear value (CPW) could inspire people towards higher quality clothing that lasts longer, by raising awareness of how quality clothing can be cheaper than fast fashion over time. (Psychology & Marketing, 2025).

🧮 How big is Mount Trendy?

Our rough-and-ready methodology

To transform the staggering weight of the world’s fast fashion habit into a flashy geographic landmark for all seasons, we’re sticking to the same cheeky, back-of-the-envelope logic we used for its predecessor, Mount Waste. While our original peak was built from the world’s discarded leftovers, Mt. Trendy is constructed entirely from the textiles, sequins, and landfill-loving fabrics that define modern fashion.

- Shape: As with its sibling peak, we’re picturing a classic, sharp cone.

- Density: Clothes are incredibly airy – all those fibers and pockets of air mean they don’t pack as tightly as steak, or even Emmental. Based on our research, we’re using an average density of 130kg per cubic meter. This reflects the lightweight nature of uncompacted textiles and synthetic fibers.

- The Scenario: For this iteration, we’ve tightened the base a bit because of the lower amount of material. We’re imagining a slightly more constrained base for our textile peak: 800m wide (about 0.5 miles).

Crunching the numbers

- First, let’s convert our 120 million tonnes into kilograms: 1.2 billion tonnes = 1.2 x1011

- 1.2 x 109 tonnes x 1000kg/tonne = 1.2 x1011kg

Next, we calculate the total volume this mass would occupy given our typical density:

- Volume (V) = Mass / Density

- V = 1.2x 1011kg / 130kg/m3 = 936,076,923m3

(That’s over 923 million cubic meters of polyester, cotton, and remorse.)

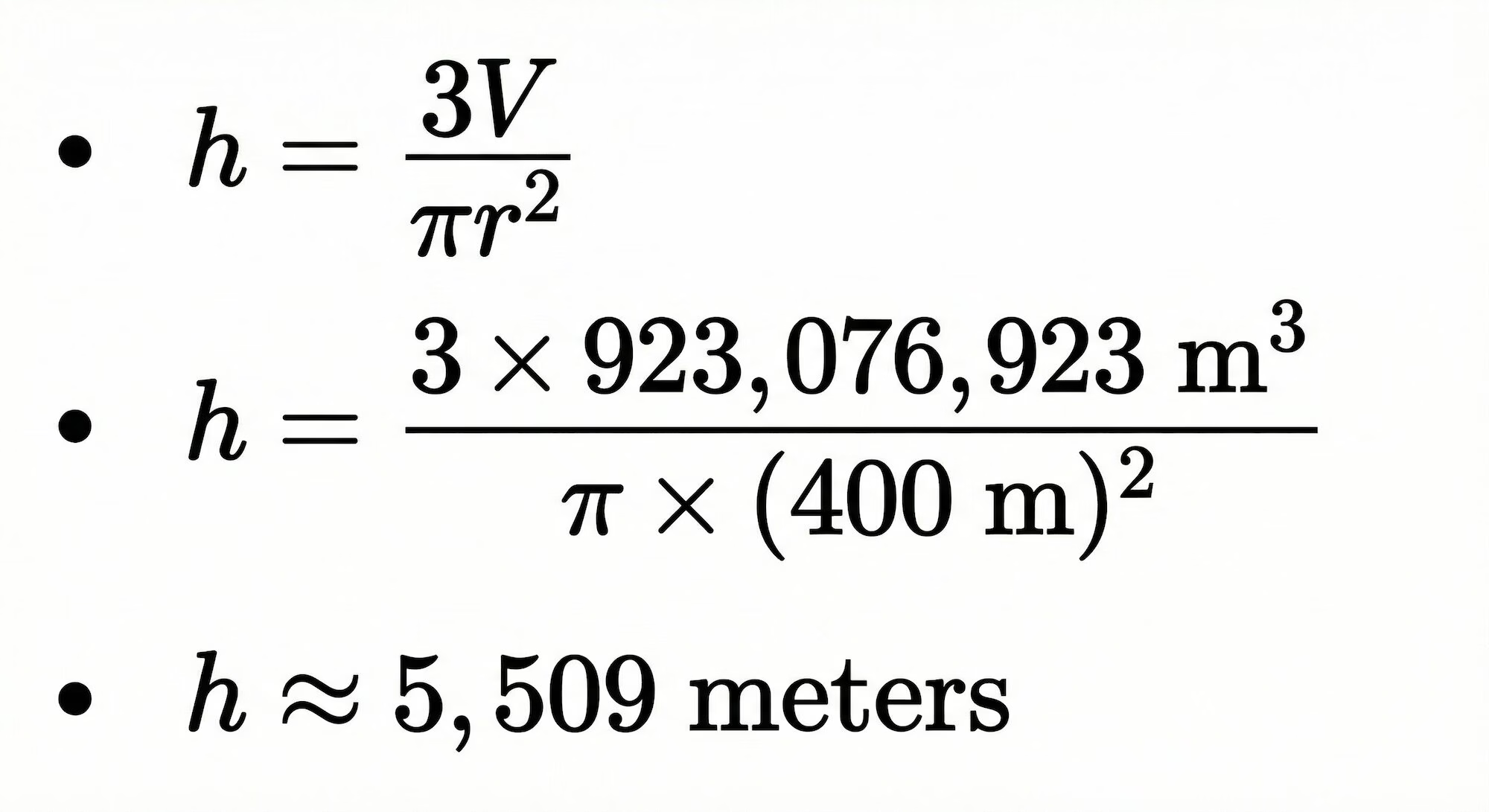

Now, for the saucy part – the height. Mt. Trendy has a base diameter of 800m, meaning a radius of 400m. Using the well-known formula for the volume of a cone (V=1/3πr2h), we can rearrange it to find the height (h):

The verdict: A needle piercing the clouds

So, how does Mount Trendy stack up? It reaches a vertiginous height of 5,509 meters (approximately 18,074 feet).

While it still looks up to the legendary, still unclimbed 9,931-meter summit of Mount Waste, the planet’s highest peak, and is also shaded by the planet’s second highest peak, Mount Everest, Mount Trendy is an epic mountain – a sharp, garish needle of discarded trends that would dominate any landscape. To put that height into perspective:

- Bigger than the Alps: At 5,509m, Mt. Trendy is nearly a full kilometer taller than Mont Blanc (4,807m). It would tower over almost every peak in Europe and North America.

- The world’s biggest department store: It’s equivalent to stacking over six and a half Burj Khalifas (828m) on top of each other. Think of all the shops you could fit in there!

Of course, a mountain of fabric this steep and narrow would likely suffer from some catastrophic wardrobe malfunctions (landslides) without some promethean engineering. But since we’re already imagining a world where we throw away 120 million tonnes of clothes a year, we’re sure that tech bros could find a way to stabilize our towering monument.

🥪 The next time you need a new look…

Even if an item looks super – remember: the facts above make it clear that fast fashion is inflicting a huge stain on our world. Looking ahead, the appetite for cheap clothing isn’t subsiding but perhaps the change can start with your style; your fly get-up – and as we said at the start of this article, the clothes from fast fashion brands are pretty shoddy anyway. As the famous quote from Vivienne Westwood goes, “Buy less. Choose well. Make it last.” That’s a reasonable mantra for the times we’re living through, mostly in clothes.

We’ll make sure to update this article with the latest studies, stats, and research. Feel free to use these to reinforce your story – wherever you’re telling it. And remember, facts alone aren’t enough to shape a convincing narrative. If you’re a better kind of fashion brand, about to tell the world about your mission, why not introduce yourself? We’ve supported businesses of all sizes to tell their stories and sustainable fashion is one of the key sectors we carve out success in.

Leave a Reply