Since you’re here then you probably already know that regenerative sustainability is about restoring, renewing, and revitalizing ecosystems and communities.

The concept is meant to address the climate crisis in a more impactful and tactical way than the long fight for sustainability has, by going beyond traditional environmental conservation. Meaning, striving for the improvement of natural resources, not just avoiding harm, as sustainability suggests. Many people feel that the idea of sustainability isn’t enough anymore. ‘Sustainability’ has been thrown around so much that the word is losing its significance. So, we need to strive for more, they say.

While regeneration is now universally being applied to fields like environmental science, architecture, urban planning, agriculture, tourism, education, finance, fashion, and business, the concept is known for its roots in agricultural practices. Let’s get a bit more into that, and how regenerative sustainability came to be what it is today.

Thousands of years ago: Indigenous roots of regenerative agriculture

There’s a false narrative that regenerative farming is a “new” concept. It’s not revolutionary or innovative. Regenerative agriculture is often based on traditional practices like permaculture, agroecology, agroforestry, intercropping, and polycultures, which are founded on the principles of indigenous farmers from around the world. Shiloh Maples, a fair food systems educator based in Detroit, puts it like this: “Regenerative agriculture is in many ways a rebranding of generations of ancestral knowledge”. These farming practices have been done for so long – about 7,000 years – in ancient communities, that it’s hard to even pinpoint specifically on the timeline.

Indigenous farming is about deep connection and interdependence of all things, and respect for the land. Even today, indigenous people safeguard an estimated 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity, and the global community can learn from indigenous people, according to the UN. And that’s exactly what’s happening here: the knowledge and practices of indigenous people are at the center of today’s regenerative agriculture system.

1970s & 1980s: Organic farming & design-thinking

Since the 40s, organic pioneers talked about the concept of soil health, which is a key tenet of regenerative farming today. Among the pioneers like Sir Albert Howard (who is considered the father of organic farming), we have the Rodale Institute, known for promoting and popularizing organic farming. By the early 80s, as a result of the growing concerns and criticisms of the lack of enforcement of organic foods, Robert Rodale coined the term ‘regenerative organic agriculture’.

Interestingly, the roots of regenerative design also emerged through agricultural practices. Along with the influence of Rodale’s principles of regenerative sustainability in organic farming, John T. Lyle translated the design principles of permaculture to the building design field.

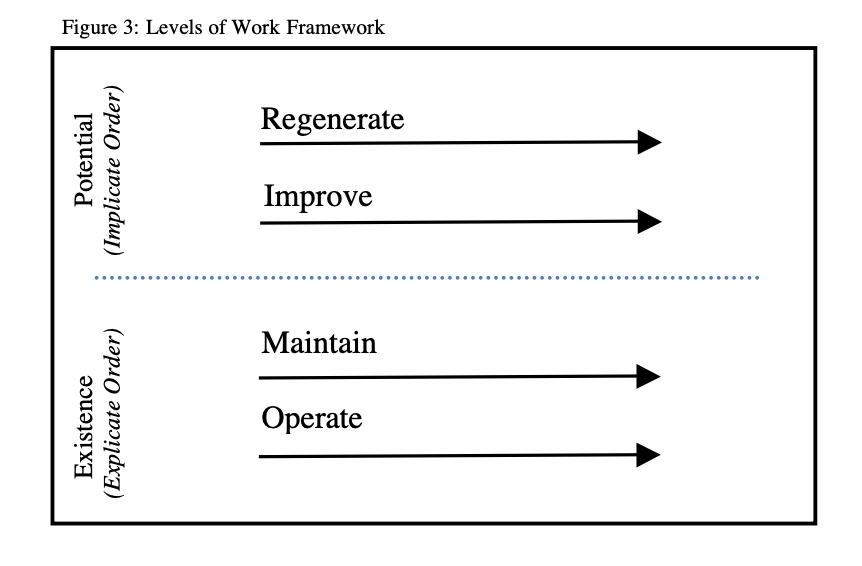

Also influential towards today’s regenerative building design principles is the work of Charles Krone, who created a new way of thinking, called ‘Living Systems Thinking’. As part of this concept, he came up with a framework consisting of four ‘levels of work’ that every living system or entity should engage in to be sustainable. Regeneration is the fourth level of work, which means that designers need to cover all the levels of work to attain regeneration.

Think of it a little like Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and self actualization, for folk.

1990s to early 2010s: The regenerative building movement

The early 1990s saw growing momentum in regenerative building development and design. In 1995, the term ‘regenerative development’ was first used by the Regenesis Group, who built on J.T. Lyle’s work and have since become a world leader in the field. Their approach quickly attracted leaders in the green building movement. From 2012, Regenesis started releasing educational offerings for sustainability professionals interested in integrating regenerative development into their practices. Their idea was that, in contrast to conventional ‘green’ building practices, regenerative building practices would catalyze positive – as opposed to neutral – environmental and social outcomes. So, not net-zero, but net-positive.

Mid to late 2010s: Widespread recognition & a surge in interest

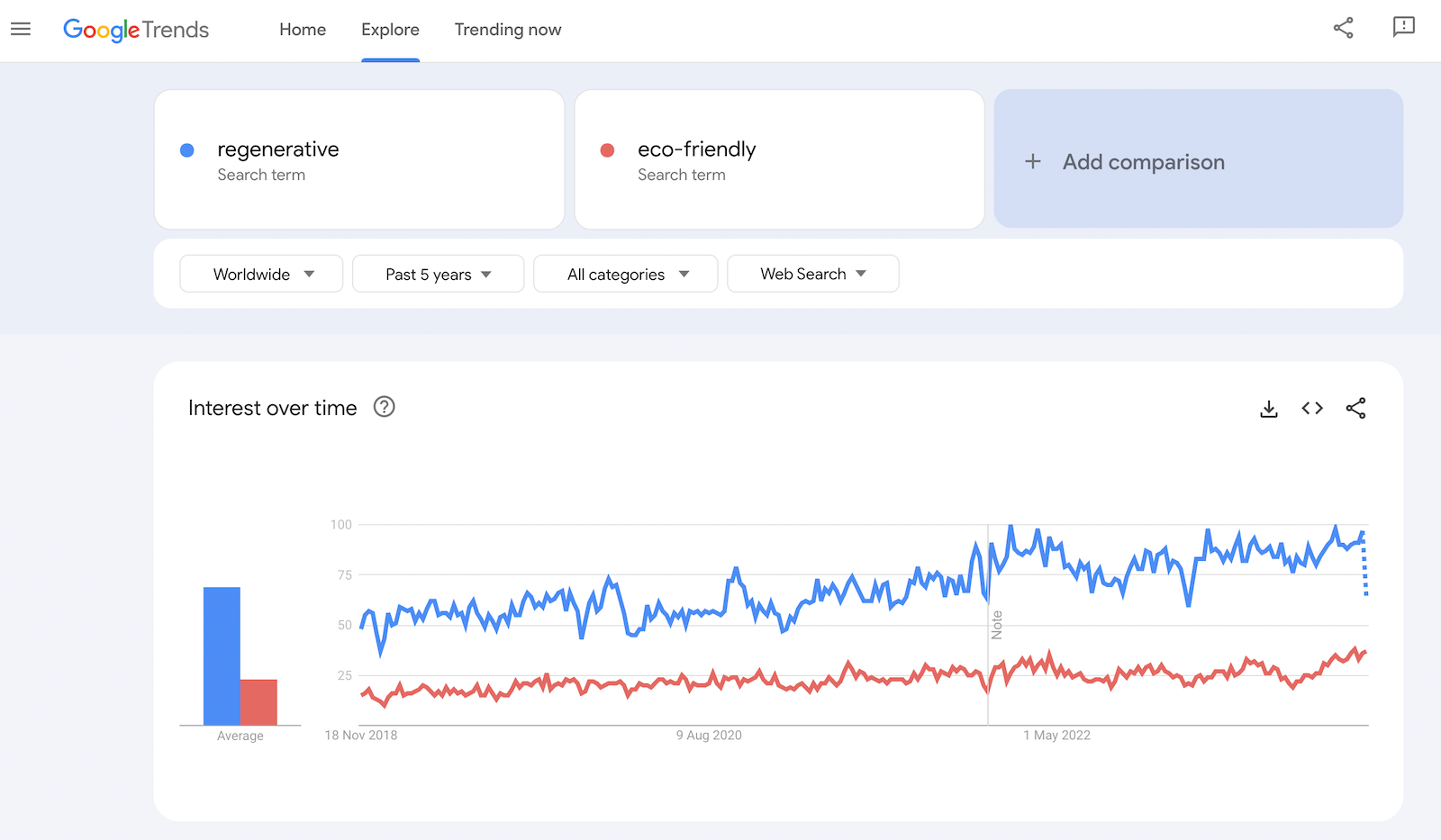

Before 2014, hardly anyone had heard of regenerative agriculture. Between the initial hype of the 1980s and this era, the concept lost its momentum and virtually disappeared from books. Since 2016, the term’s occurrence has increased dramatically in books, news outlets, and the internet.

In 2018, marketing giant Wunderman Thompson published a trend report called ‘The New Sustainability: Regeneration’. The report stated: “Doing less harm is no longer enough. The future of sustainability lies in regeneration: seeking to restore and replenish what we have lost.” This was the spark that made the mainstream take note. Shortly after, there was a surge in interest which reflects the now widely adopted use of the concept by all kinds of industries. With a marketing agency as large and influential as Wunderman Thompson, it’s no surprise that ‘regenerative sustainability’ hit the cultural mainstream. Brands became aware that this is a new term they could use to target customers. In 2019, Diana Martin from the Rodale Institute cautioned, “It’s the new buzzword. There is a danger of it getting greenwashed.”

Now: A great deal of attention, plus pioneering practices

Now we know that regenerative sustainability is not new. In the world of regenerative agriculture, as scientists have been realizing in the last decade that soil health is critical to climate mitigation, we’re straying away from conventional agriculture and back to more traditional methods – for which we have indigenous people to thank. And now we have modern scientific knowledge, and we see more innovative regenerative practices. One recent development is Australian biotech startup Loam Bio’s microbial seed coating, which “supercharges a plant’s natural ability to store carbon in soil”.

There are also a rising number of startups using AI to implement pioneering regenerative practices, at scale. Take Australia’s Flying Fish, for example, who have just implemented the largest ever reef survey – augmented by AI – to assist with the regeneration of coral. Into the future, we’re likely to see AI getting more involved.

But with the growth of regenerative sustainability, we must beware of companies that are falsely trying to brand themselves as such. Some of the most polluting corporations are trying to hop onto the regenerative bandwagon, like JBS, the world’s largest meat producer; McDonald’s, notorious for their greenwashing stunts; Cargill, the global food corporation whose practices have been linked to deforestation; and Nestle, surely one of the most suspicious companies in the world. Territorial authorities are also marking regeneration efforts as ‘increased housing’ or ‘increased public spaces’.

Of course, sustainability is a transition, progress versus perfection, and global brands can get involved too. But there needs to be a little more perspective. Where does the truth lie? After all, when consecutive COPs seem to be making little impact and greenhouse gas emissions are reaching record levels – we need to be on our guard for who’s regenerating (and who’s just making things worse while claiming they’re making things better). We’re running out of time.

Now that you’ve uncovered the history of regenerative sustainability, hopefully that’ll help assess the use of the word more critically. And as with anything related to sustainability, certifications and standards help avoid any kind of corporate catfishing. Remember the Rodale Institute we mentioned? They’ve now created, along with their alliance that includes brands like Patagonia and Dr. Bronner’s, the Regenerative Organic Certified standard – so look out for their symbol!

Leave a Reply