The world is in a frantic race towards clean energy. And to no one’s surprise.

We’ve made a fine mess with coal, oil, petroleum, and the rest of the fossil fuel gang.

Renewables are crucial to fight climate change and global warming. Over time, the ways we’ve harnessed them to meet our energy needs have evolved significantly.

Unlike other “history of” topics we’ve covered, this one is a bit different. Rather than moving simply through time, we first go quickly into the four main types of renewable energy.

So skip ahead to one that interests you before moving to the moment when things start to come together:

- Solar energy

- Wind energy

- Hydroelectric energy

- Geothermal energy

- The 1970s: an inflection point

- Renewable energy today

- The future

- Timeline infographic

Solar energy

Let’s talk about the sun first.

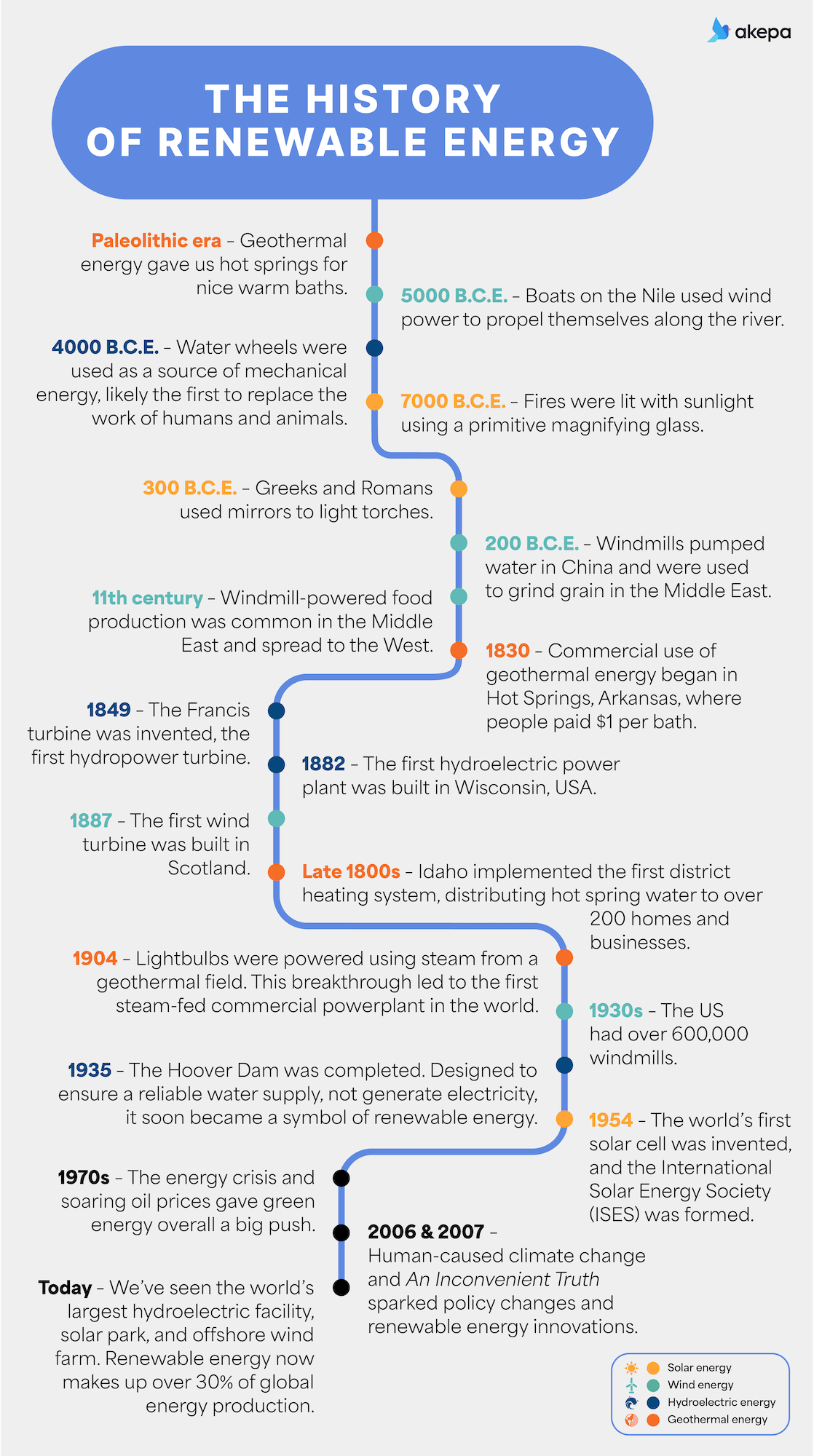

The roots of solar go back to 700 B.C.E. when folk started lighting fires with sunlight using a primitive magnifying glass. Fast-forward to 300 B.C.E., and the Greeks and Romans used mirrors, known as “burning mirrors,” to light torches. The same was happening in China by 20 B.C.E.

These ancient methods don’t quite look like today’s solar power, but they share the same core idea around renewable energy: using a naturally-occuring resource that replenishes itself faster than we consume it.

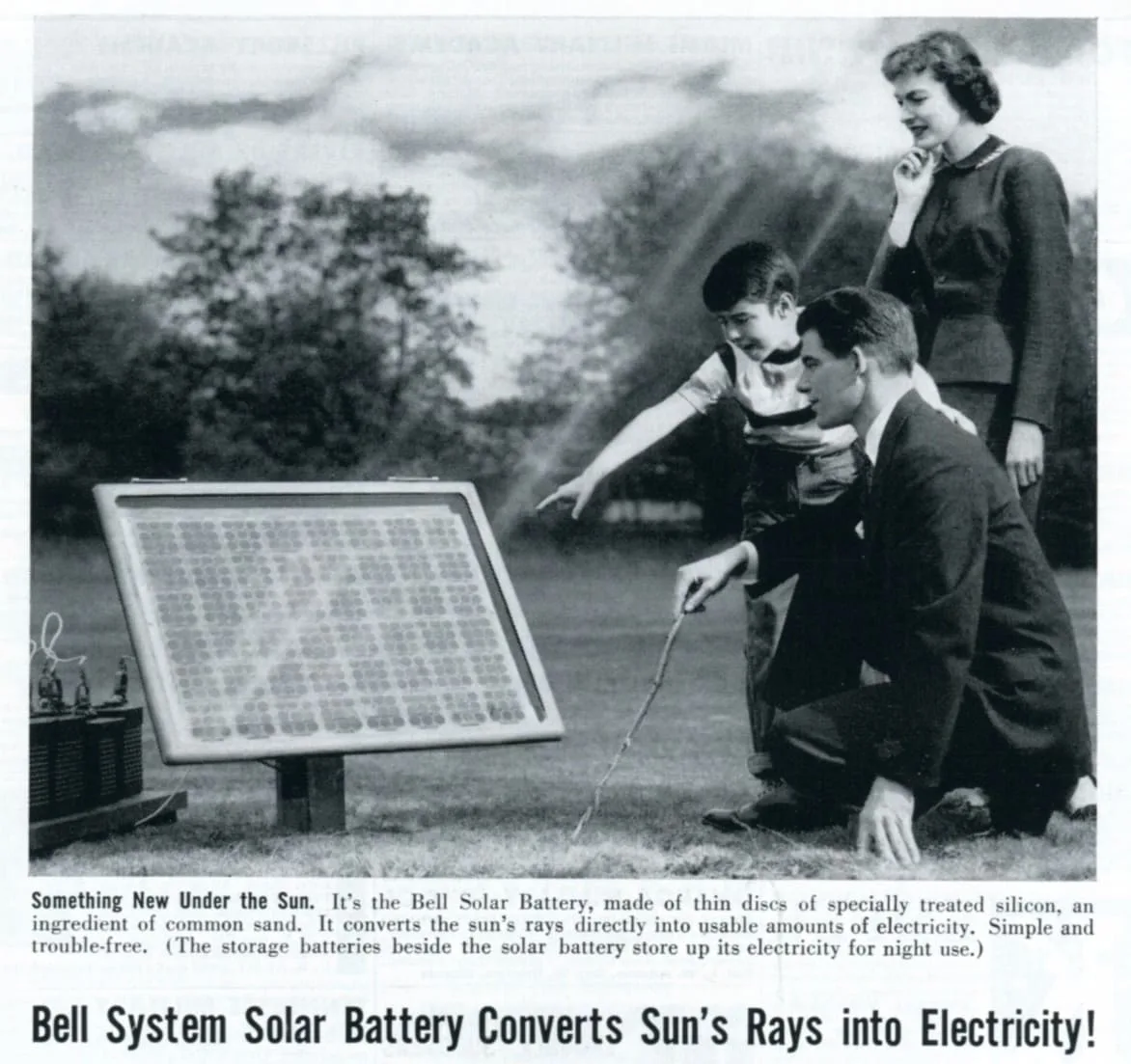

The late 1800s saw the early foundations of the solar cell, but modern technology was only developed in the 20th century. In 1954, the International Solar Energy Society (ISES) was formed and the world’s first solar cell was invented. The energy crisis and soaring oil prices of the 1970s gave solar energy a big push – but more on this decade later.

Since the 1990s, industry innovation and supportive government policies have driven the growth of solar energy and its widespread adoption.

Wind energy

Wind is another with a longstanding history.

In ancient times, people harnessed the wind for practical uses. As early as 5000 B.C.E., boats on the Nile used wind power to propel themselves along the river. By 200 B.C.E., windmills in China pumped water. In the Middle East, vertical axis windmills were used to grind grain. And by the 11th century, windmill-powered food production was common in the Middle East.

After spreading to the West, over 100,000 windmills dotted the landscapes of England and Central Europe. In 1590, windmills were incredibly popular in the Netherlands. The Dutch adapted them for tasks like making paper and draining lakes (to reduce floods). In the 19th century, settlers in America used windmills to pump water for farming.

Eventually, wind energy transitioned from mechanical uses to generating electricity. In 1887, James Blyth, an electrical engineer, built the first wind turbine in Scotland. Skip to 1888, Charles Brush in Ohio developed his own turbine. By the 1930s, the U.S. had over 600,000 windmills.

Just like solar, interest in wind power surged during the energy crises of the 1970s.

Hydroelectric power

Then there’s the third element: water.

Water as a source of mechanical energy supposedly began in Ancient Rome with the water wheel, as humans and animals no longer needed to do all the pulling. Water to generate electricity only happened centuries later.

In the mid-1800s, British-American engineer James Francis invented the Francis turbine, paving the way for technological advancements. In 1882, the first hydroelectric power plant was built in Wisconsin, USA.

A quick lesson for some – these plants work by capturing the energy of falling water. Water is stored in a reservoir and released by a dam, which controls the flow. That flowing water turns a turbine, powering a generator to create electricity that gets distributed through transmission lines.

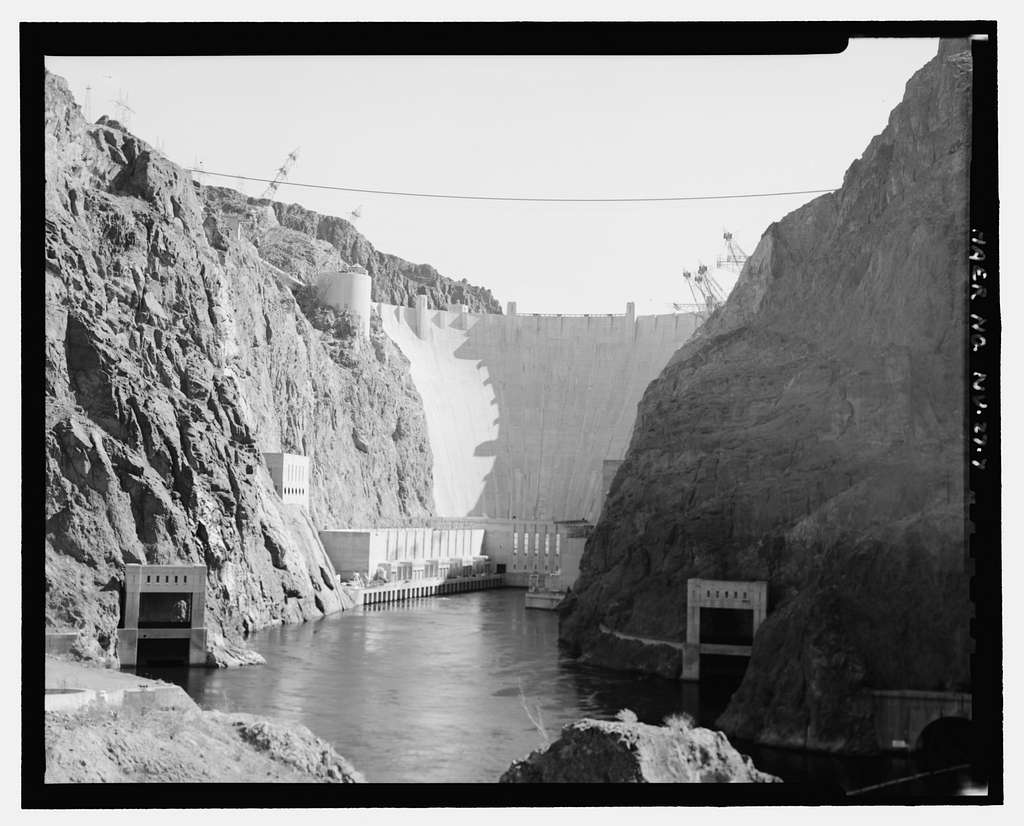

Water wheels and small hydroelectric plants continued to gain popularity and become more effective over time. Their use slowed during the Industrial Revolution due to the rise of coal burning and oil drilling. But in 1935, the Hoover Dam came into the picture.

The iconic structure was designed mainly to control the flow of the Colorado River and ensure a reliable water supply for Southern California and Arizona. The generation of energy was nothing more than a means to an end, a way to recover building costs. Now it holds much more significance as renewable energy becomes a necessity.

Geothermal energy

Earth is the last piece of the puzzle. In this case, we’re talking about using heat that comes from underneath the surface.

Humans have been tapping into geothermal energy since the Paleolithic era. Back then, it was hot springs for a nice warm bath. And it was free.

Commercial use came in 1830. The story goes that in Hot Springs, Arkansas, people could enjoy a dip in baths fed by three hot springs for $1. In the 1890s, the state of Idaho made history with the first-ever district heating system, distributing hot spring water to over 200 homes and businesses.

The U.S. had made strides, but then Europe took the lead in geothermal power. In 1904, Italian Prince Piero Conti (yes, he was a royal) managed to power lightbulbs using steam from Tuscany’s Larderello geothermal field. This breakthrough led to the first steam-fed commercial powerplant in the region – and the world.

Geothermal energy, like other green energies, only started to gain momentum in the 1970s.

The 1970s: an inflection point

In the past few decades, renewable energies have seen a huge jump. Many believe the oil crises of the 1970s were the wake-up call that made people take the matter seriously. Plus, increased awareness of environmental issues.

An energy crisis happens when demand outstrips supply. Take 1973, for instance. The U.S. faced a trade ban from oil-rich countries because of it its involvement in the Yom Kippur War. That led to tension with nations like Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Iraq, and Qatar. As a result, oil prices shot up by 300 percent in just a year.

This had a massive impact on transportation. Cars became much more fuel-efficient. Interest in mass transit systems soared. And there was a big push to harness renewable energy like wind and solar.

Renewable energy today

In 2006, former US Vice President Al Gore released the documentary An Inconvenient Truth, sparking a wave of policy changes and innovations aimed at combatting global climate change. The following year, the IPCC published a report confirming that human activity was both causing and speeding up this dire problem.

As the environmental movement gained momentum and concerns about the impact of fossil fuels grew, interest in renewable energy skyrocketed.

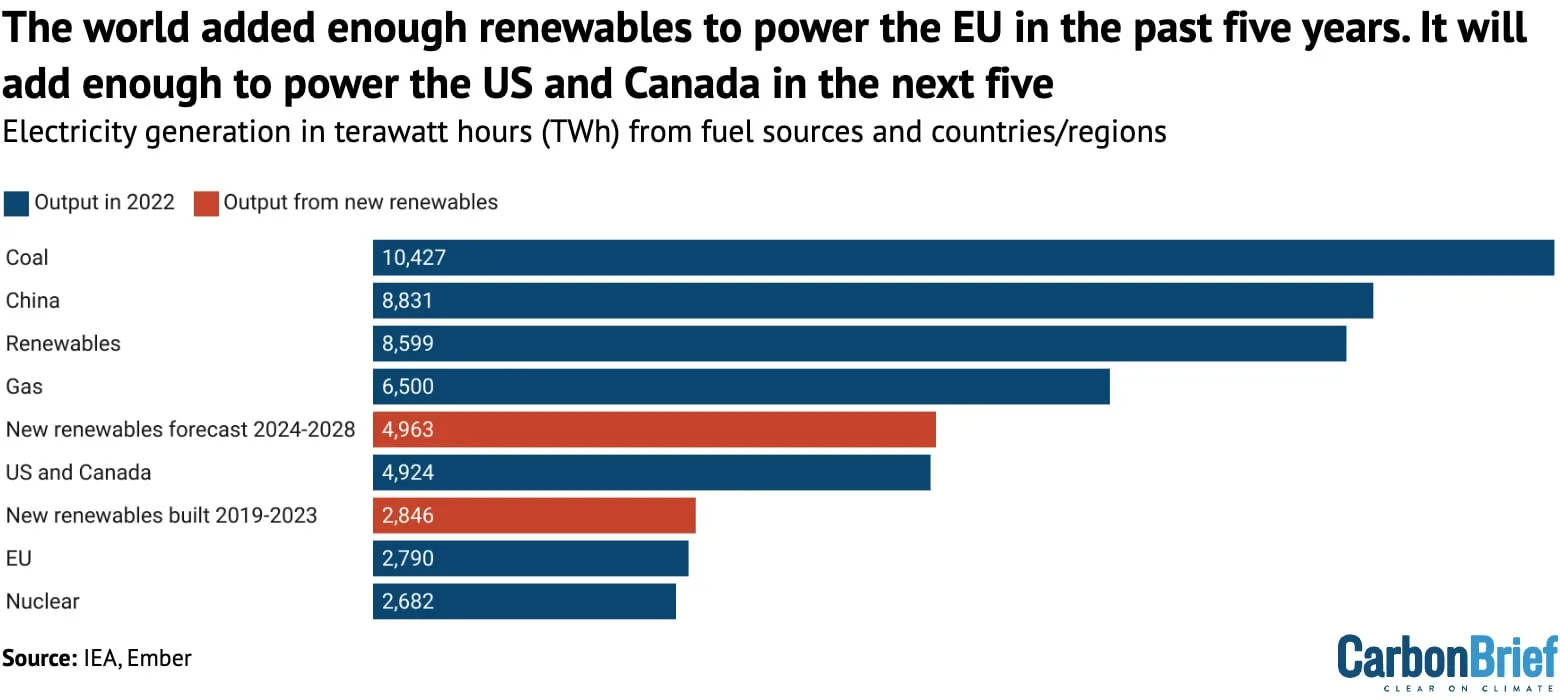

We’ve seen record-breaking developments, like the creation of the world’s largest hydroelectric facility, solar park, and offshore wind farm. And in 2023, the addition of new renewable energy capacities jumped by nearly 50%, making up over 30% of global energy production.

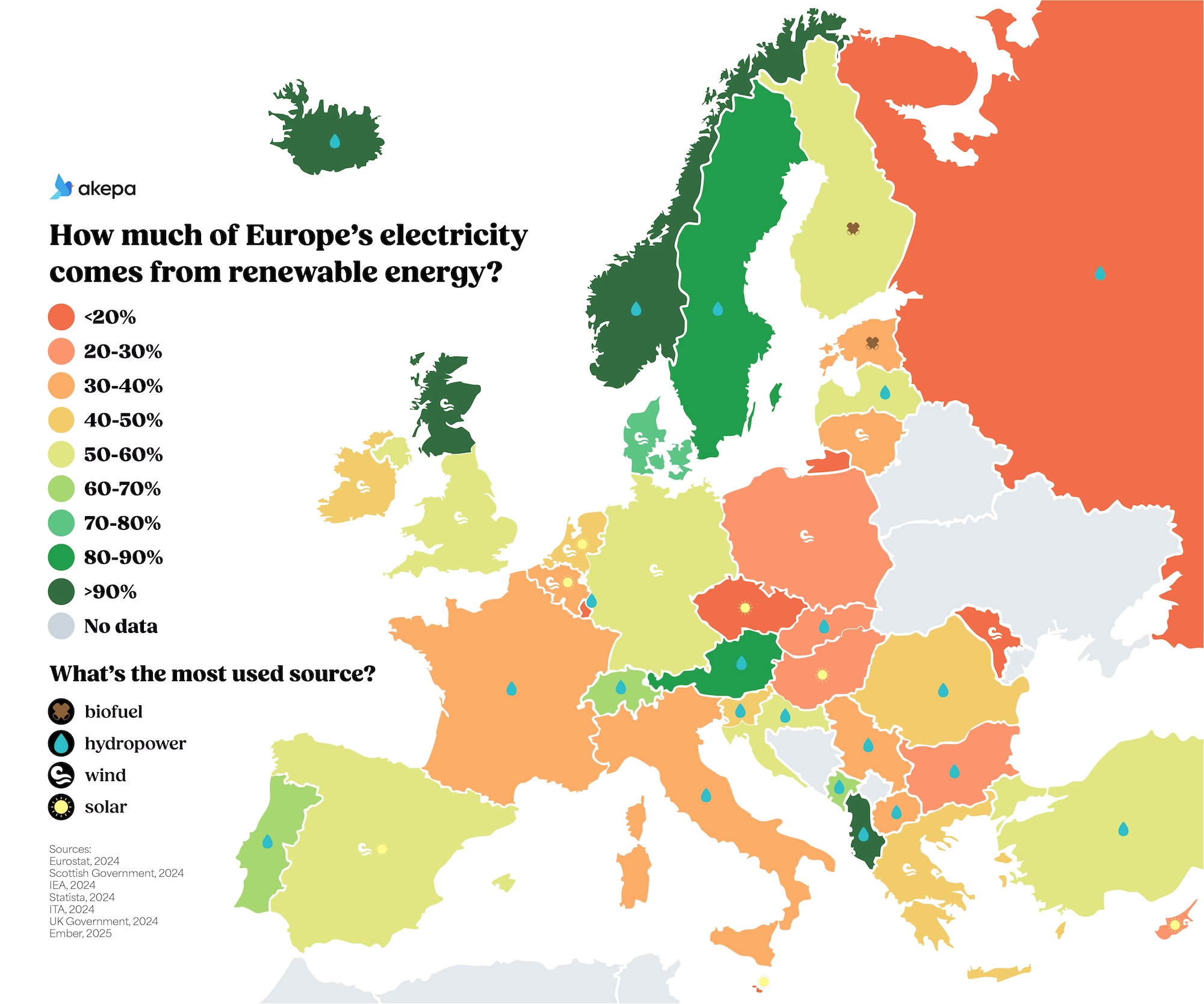

In early 2025 it was reported by thinktank Ember that worldwide clean electricity has surpassed 40% for the first time ever, driven by record investment in renewables. The overall net total within the EU reached 47% in 2024. Europe is also rapidly emerging as a solar superpower and many nations are already generating the majority of their electricity from renewable sources. Despite the growth in solar, though, hydropower is still doing most of the heavy lifting.

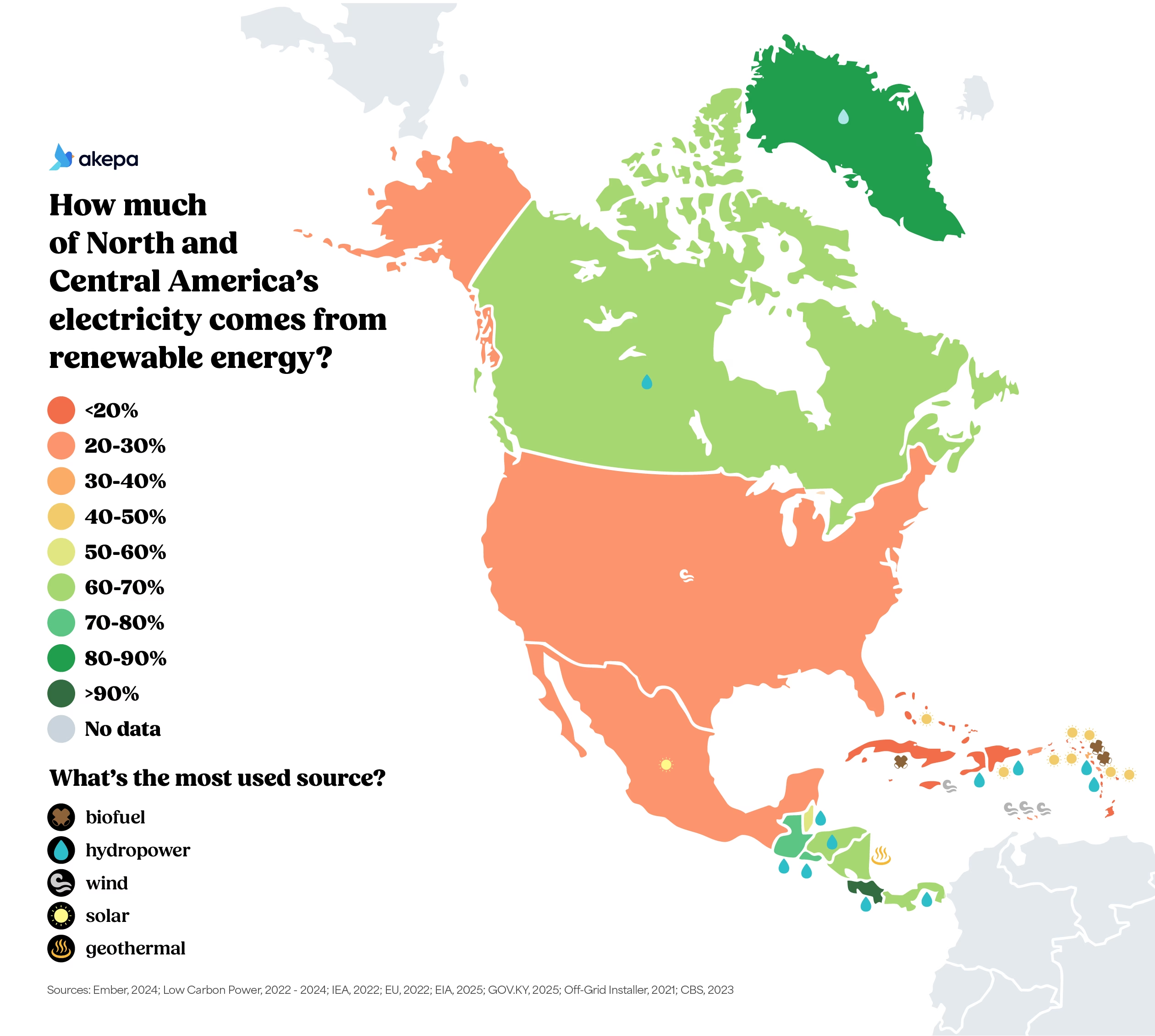

It’s not all good news and boom. The promising growth in some regions is counteracted by diminishment in others. The US is one outlier in the present era, as the administration shifts policy away from renewables and towards fossil fuels. Take a sweeping phase-out of subsidies and tax credits – putting billions of dollars of projects at risk.

When you compare the stats on electricity generation with other regions in North America, and against Europe, the US is lagging behind – despite often positioning itself as the global pioneer when it comes to innovation.

Yet, despite setbacks in some parts of the planet, it seems that renewable energy is on an unremitting ascendancy. In the first half of 2025 investment in renewable energy hit a new record of $386 billion.

What the future holds

Unfortunately, despite the record growth in renewable energy, fossil fuels still dominate the overall energy landscape.

The bright side is that many countries and companies are heavily investing in new technologies and committing to renewable energy sources. And we’re seeing the rewards through the gains in green energy output.

One of the biggest hurdles for the industry is still storage. Since the sun doesn’t always shine and the wind doesn’t always blow, storing energy for later use can be tricky.

Another is cost. While renewable energy has become more affordable over the years, it’s still pricier than the fossil fuel alternative. Technology needs to improve and production needs to scale up at much faster rates. Add to that while developed countries are moving in the right direction, less developed countries – many of whom suffer disproportionately from the negative effects of climate change – face a massive financing gap.

If we’re to have any chance of achieving those 2030 and 2050 climate targets, progress is needed everywhere for everyone.

And there you have it. More than 2 thousand years of history in the evolution of renewables.

It’s not perfect and key challenges remain, but we at Akepa do our best to believe in a future where less homes rely on dirty power as the grid is filled with cleaner energy sources. This includes working alongside sustainably-driven brands, businesses, and other organizations, so that they stand out among the rest.

Leave a Reply