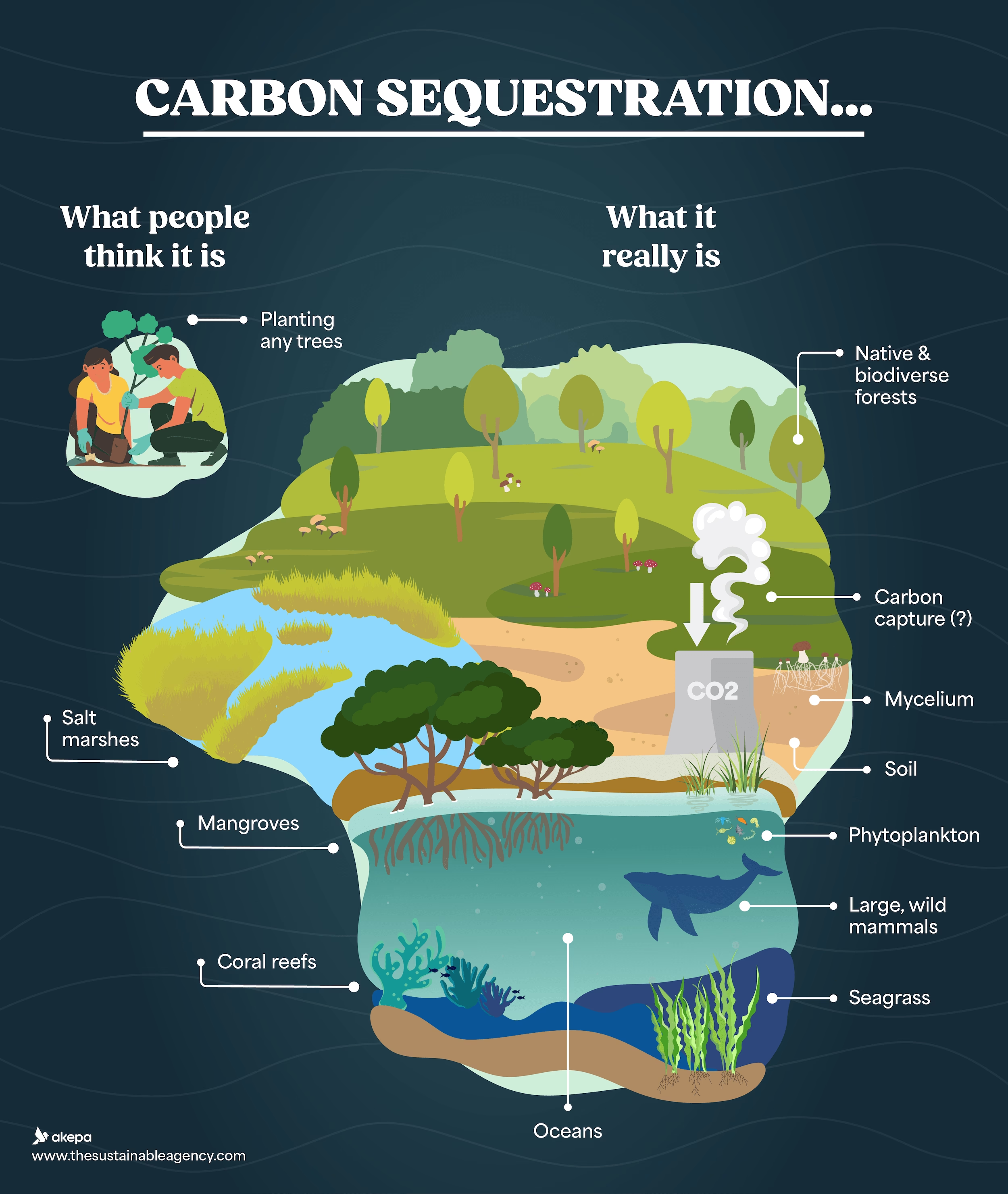

“We’ll plant a tree for every purchase,” they said. Sounds great on the surface! Everyone knows planting trees helps remove carbon dioxide from the air – and carbon dioxide is bad for the planet.

Not so simple. Carbon sequestration – or carbon removal – is not about planting just any ol’ tree. Tree planting schemes could really be doing more greenwashing than carbon-removing if their focus is on planting non-native trees and monocultures (single-species plantations). Non-native plants can be beneficial but native plants can’t be neglected as they often outperform the carbon storage capacity of monocultures. The number and combination of species planted must be intentional and appropriate to the location.

Unfortunately, many tree planting schemes focus on creating monocultures where only one species is planted over a large area. This is the cheaper and easier option but it doesn’t achieve forest and wildlife restoration and instead leads to a loss of biodiversity. According to researchers from University College London and the University of Edinburgh, 45% of the evaluated worldwide government commitments around tree planting involved “planting vast monocultures of trees as profitable enterprises.”

This is a reminder that there’s a lot more on this planet that can sequester carbon. Let’s take a stroll through some of the earth’s carbon sinks:

Native and biodiverse forests

There are issues with tree planting but that doesn’t mean that these schemes are worthless entirely. Nevertheless, native and biodiverse forests are vital for carbon sequestration. Countless studies show that native trees capture more carbon than non-native ones.

Don’t just take our word for it, a 2023 meta-analysis found that forests planted with four native tree species were 70% more effective in carbon storage than the average monoculture. Another study in 2022 revealed that replacing non-native palms with native palms stored more carbon, enhanced biodiversity, and reduced coral disease. Even more recent research found that forests planned with five native tree species stored 57% more carbon above ground than monocultures after 16 years of growth. The evidence seems crystal clear.

Carbon capture

Carbon capture involves collecting carbon dioxide from industrial emissions or power plants and trapping it underground. This prevents the CO2 from affecting the atmosphere.

The effectiveness of carbon capture, however, is highly debated. Some studies suggest it is inefficient, capturing only 10-11% of CO2 emissions compared to the 85-90% boasted by many CO2 technologies.

While the technology shows potential, the oil and gas industry is overly reliant on it as a solution for cutting emissions. Meanwhile, new carbon capture technologies remain costly and unproven at a large scale, making them a controversial approach to addressing climate change.

For now we’ll give them the benefit of the doubt. But they’re only ever going to be part of the equation. Just like indigenous communities protecting natural habitats are underrated, climate bros who’re all about fancy innovations are way overrated.

Soil

Healthy soils are one of Earth’s most powerful carbon sinks. Through a process known as soil organic carbon sequestration, they lock carbon from decomposing plants and animals. You may be shocked to hear that soils contain more than three times the amount of carbon that’s in the atmosphere. Approximately 2.5 gigatons of CO2.

With that said, careless agricultural practices like extensive tilling and monoculture farming have led to soil degradation, releasing stored carbon into the air. But there is hope. Methods such as regenerative agriculture, reduced tillage, and cover cropping have the potential to restore organic matter in the soil, boosting long-term carbon storage.

For example, farmlands managed with regenerative practices can sequester up to 3 metric tons of carbon per hectare annually. Considering the billions of hectares of farmland worldwide, the widespread adoption of these practices could make a decent dent on atmospheric carbon levels.

Mycelium

Within the soil, mycelium – the network of fungal threads found within soils and ecosystems – plays an understated but critical role in carbon sequestration.

Imagine a classic red and white toadstool. Underneath it, is an underground network of carbon highways that can break down organic matter into carbon-rich compounds and lock it in the soil for centuries.

A key feature of mycelium is its symbiotic relationship with plant roots, called mycorrhizal networks. They allow fungi to exchange nutrients with plants, which results in healthier vegetation that absorbs more carbon dioxide. This is a job done well: research has shown that mycorrhizal fungi may store up to 13.12 gigatons of carbon globally. That’s more than the annual emissions of the United States.

Although mostly invisible to us, mycelium contributes impressively to carbon storage and overall ecosystem function. Protecting and encouraging fungi-rich soils could help to step up the battle against climate change by recruiting an elite new subterranean regiment.

And who doesn’t love a good mushroom, anyway?

Large, wild mammals

Large wild mammals such as elephants, bison, and whales have unique and often overlooked roles in natural carbon sequestration. By their grazing and migration patterns, they help maintain the health of ecosystems, indirectly boosting carbon storage.

Studies show that they can increase an ecosystem’s carbon storage by up to 250%. Protecting these species is not just about wildlife conservation but also about safeguarding vital carbon sinks.

Phytoplankton

Phytoplankton, microscopic marine organisms, play a starring role in carbon sequestration. Like plants, phytoplankton use photosynthesis to absorb carbon dioxide from the air while releasing oxygen.

Don’t be fooled by their tiny size! These oceanic organisms are responsible for most of the carbon transfer from the atmosphere to the ocean, which is itself responsible for storing around 30% of CO2 emissions. When they die, much of their carbon literally sinks to the ocean floor, providing long-term storage. However, climate change and pollution threaten phytoplankton populations, just like bigger forms of biodiversity on earth (e.g. those large wild mammals we’ve just spotted).

It’s another (not so friendly) reminder that biodiversity and climate change are inexorably linked.

Seagrass, salt marsh & mangroves

Coastal wetlands may cover less than 1% of the ocean, but they store over 50% of its seabed carbon reserves. Seagrass, salt marshes, and mangroves in particular sequester carbon at rates up to four times faster than forests.

Yet, coastal development for housing, ports, and other commercial facilities is destroying these habitats at an alarming rate. This destruction not only reduces their ability to capture carbon but also releases previously stored carbon, adding more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere

Coral reefs

Coral reefs may not directly store large amounts of carbon, but they support biodiversity which helps maintain marine ecosystems that do sequester carbon. Healthy reefs benefit ecosystems reliant on seagrass and mangroves, multiplying their carbon-capturing talents.

What’s more, reefs act as protective barriers for coastal habitats, reducing their damage from erosion and extreme weather events. Protecting reefs plays a critical role in maintaining other coastal carbon sinks.

Oceans

Last but not least and in fact most: the ocean itself is the planet’s largest carbon sink, absorbing around 30% of human-produced CO2 emissions. Yet, this comes with a downside. The increased absorption of CO2 is causing ocean acidification, a process that disrupts marine ecosystems and reduces the ocean’s ability to sequester more carbon.

Understanding and mitigating this challenge is vital to maintaining the ocean’s critical role in combating climate change.

And we mustn’t forget the key role of transferring CO2 from the atmosphere to the ocean, that Phytoplankton play – which we covered earlier.

Carbon sinks run the range, from fungi and soils to whales and phytoplankton. It’s not just about planting trees and in fact is not just about trees full stop. Protecting the planet’s many natural carbon sinks will require all the connections to be covered in order to find a less fiery future.

Let’s try and get it done right and we suppose that understanding the landscape is a decent first step. We’ve done our best but of course we couldn’t cover everything in a short post. If you feel we’ve overlooked something, let us know!

Leave a Reply