Fan or not, it’s hard to argue against the ability of sport to bring people together. From the largest tournaments on the world stage to niche athletic events, differences are bridged, and conflicts are overcome out of respect for the game and the athletes.

I’ve experienced this firsthand in my home country of Canada, where entire communities brave temperatures below -30 to watch athletes fly through the crisp air, facing frozen fingers and toes just to be part of something we love.

But beneath those moments of spectacle lies a subtler game; not one played on the pitch or the track, but in the boardrooms of governments and global corporations.

Sportswashing: using sport to clean up a tarnished image.

The word itself is relatively new, likely coined in 2015 regarding Azerbaijan’s hosting of the European Games during what Amnesty International called “the worst 12 months of repression since the country gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991”. It describes efforts to host, sponsor, or invest in sporting events as a way to distract from human rights violations, corruption, or social inequality. In other words: managing reputation through athletic spectacle.

Sport as soft power

Few cultural forces command the kind of emotional loyalty as sport. It unites families, fuels national pride, and creates stories that cross borders and languages. Because of that, it transcends entertainment; it’s soft power.

The world takes notice when a country hosts or a company sponsors a major tournament. Images of modern stadiums, smiling fans, and reputable organisations begin to shape how we perceive them. After all, if the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) or the Federation Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA) can work with these countries or brands, how bad can they be?

That’s the logic behind sportswashing: if you can associate your country or company with the ideals of sport, you can rewrite the story being told about you.

Here are some examples of it in the real world:

Qatar’s World Cup

The 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar might be the most famous example of sportswashing in recent memory.

When FIFA first announced Qatar as the host nation in 2010, the response was utter disbelief. FIFA had set no conditions about protections for migrant workers, nor were human rights for journalists or discrimination against women and the LGBTQ+ community considered. Additionally, there were concerns about the country’s lack of football tradition, its searing summer temperatures, and its limited infrastructure. Over the next decade, Qatar poured an estimated $220 billion into new stadiums, hotels, roads, and even a brand-new city.

The official message was of progress and inclusion: a new, global Qatar ready to welcome the world. But investigations into the treatment of migrant workers told another story of poor conditions, withheld wages, and preventable deaths. Reports from Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch described labour systems that left workers vulnerable and voiceless. A 2021 analysis by The Guardian found that over 6,500 migrant workers died during the 10-year lead-up to the World Cup.

Yet for a month, the world tuned in to a beautifully choreographed celebration of football. By the time Argentina lifted the trophy, the conversation had shifted from exploitation to Messi’s legacy. Meanwhile, Minky Worden, director of global initiatives at Human Rights Watch, was calling it “the deadliest major sporting event, possibly ever, in history.”

Saudi Arabia’s sporting revolution

Saudi Arabia has taken the concept of sportswashing and expanded it into a full-scale national strategy. Under Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s Vision 2030 plan, the kingdom is spending 1.3 trillion USD (yes, trillion with a T), including heavy investments in sport such as buying football clubs and launching new global tournaments.

One controversial example is the Saudi Public Investment Fund’s 2021 acquisition of Newcastle United, a beloved English Premier League team with a fiercely loyal fan base. With that, the club’s fortunes changed: new funding, big signings, and a path back to relevance. For many fans, long starved of success, the moral questions around ownership quickly became background noise.

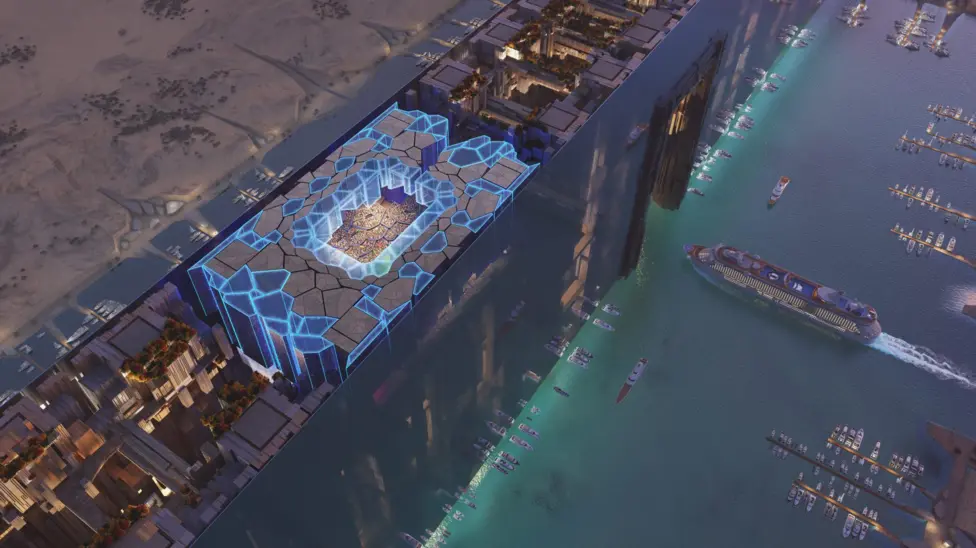

Vision 2030 has even helped turn Ronaldo into the first billionaire footballer after lucrative signings with Al-Nassr FC in an attempt to grow the sport in the region. At the same time, Saudi Arabia has created LIV Golf, a rival tour to the PGA, offering astronomical prize money to attract top players, hosted heavyweight boxing matches, eSports championships, and Formula 1 races. Its investment in the impressive Qiddiya Speed Track is sure to turn heads as well.

Each event and piece of infrastructure adds a layer of modernity, or even futurism, to the country’s international image, allegedly at the cost of 21,000 migrant worker deaths between 2017 and 2024. Saudia Arabia’s ambitions seem in sharp contrast with the record it continues to set on human rights, freedom of expression, and gender equality. Only time will tell how sports federations respond, but it isn’t looking promising given that it is the designated host for the 2034 FIFA World Cup.

Gazprom and UEFA’s quiet partnership

The Russian energy giant Gazprom was one of the Union of European Football Associations’ (UEFA) most visible sponsors for a decade. Its logo lit up Champions League broadcasts, was plastered throughout stadiums, and appeared alongside football’s biggest names. For most fans, it was just another corporate emblem, but for Russia, it was a top-tier strategic move.

Gazprom is majority state-owned and central to the Kremlin’s economic and geopolitical influence. Through sport, Russia projected a message of modernity and legitimacy, using European football to soften its reputation and divert attention from allegations of corruption, environmental damage, and foreign policy aggression.

The relationship was mutually beneficial: UEFA gained a wealthy sponsor, and Gazprom gained access to millions of viewers and a positive cultural association. Even as journalists reported on Russia’s suppression of dissent and its 2014 annexation of Crimea, Gazprom’s branding stayed on European screens, offering a gleaming image of partnership.

UEFA finally cut ties in 2022 following the invasion of Ukraine, putting an end to a deal that earned UEFA over 300 million USD. By then, Gazprom’s presence in football had already served its purpose, demonstrating how easily European sport can become a platform for political image management when ethics take a backseat to funding.

The role of institutions and brands

Sportswashing doesn’t work without cooperation. Governing bodies like FIFA, the International Olympic Committee (IOC), and Formula 1 frequently defend their choices of host nations by appealing to sport’s universal ideals: unity, inclusion, and dialogue with those with whom we disagree.

Behind those statements are complex financial realities. Hosting contracts, sponsorship deals, and broadcast rights are worth billions, and the almighty dollar often prevails over ethics.

Corporations, too, play their part. When a global brand sponsors an event in a repressive country, its logo becomes part of that country’s rebranding effort. It signals to viewers that what they’re watching is legitimate, mainstream, and uncontroversial. In that way, business interests quietly reinforce political agendas.

Breaking the cycle

So, what’s the alternative? Refusing to watch? Boycotting every event with a questionable host? Probably not realistic.

But awareness matters. When fans, journalists, and athletes ask questions about who’s funding an event, how workers are treated, or what rights are being suppressed, it becomes harder for powerful actors to hide behind the glamour of sport.

Transparency initiatives and independent monitoring can help, as can public pressure on governing bodies to apply consistent human rights standards when awarding tournaments.

There’s progress: after years of criticism, FIFA now includes human rights criteria in its bidding process, and athletes’ voices carry more weight than ever. The IOC released their human rights framework in 2022. It’s hard to believe it took so long, but at least things are moving in the right direction.

Change is slow, and money and appearances are powerful motivators, but the more sport brings us together, the more influence we have to make sure it sticks to the values we expect.

Leave a Reply