€50,000.

That’s how much we’re estimated to lose in a lifetime due to planned obsolescence. It’s said that 99% of our products are planned to be obsolete before their time.

For almost a century, companies have agreed that growth comes from selling more. The more things bought, the stronger the economy. Planned obsolescence was devised as a strategy to sell more. It’s why our phones start slowing down after the three-year mark, why our furniture feels disposable, and why our clothes rip or wear out so quickly. It’s also why many things aren’t easily repairable. They simply weren’t designed to be repaired.

How’d we get here? Let’s take a look at the timeline and then we’ll discuss the impact of this sneaky strategy.

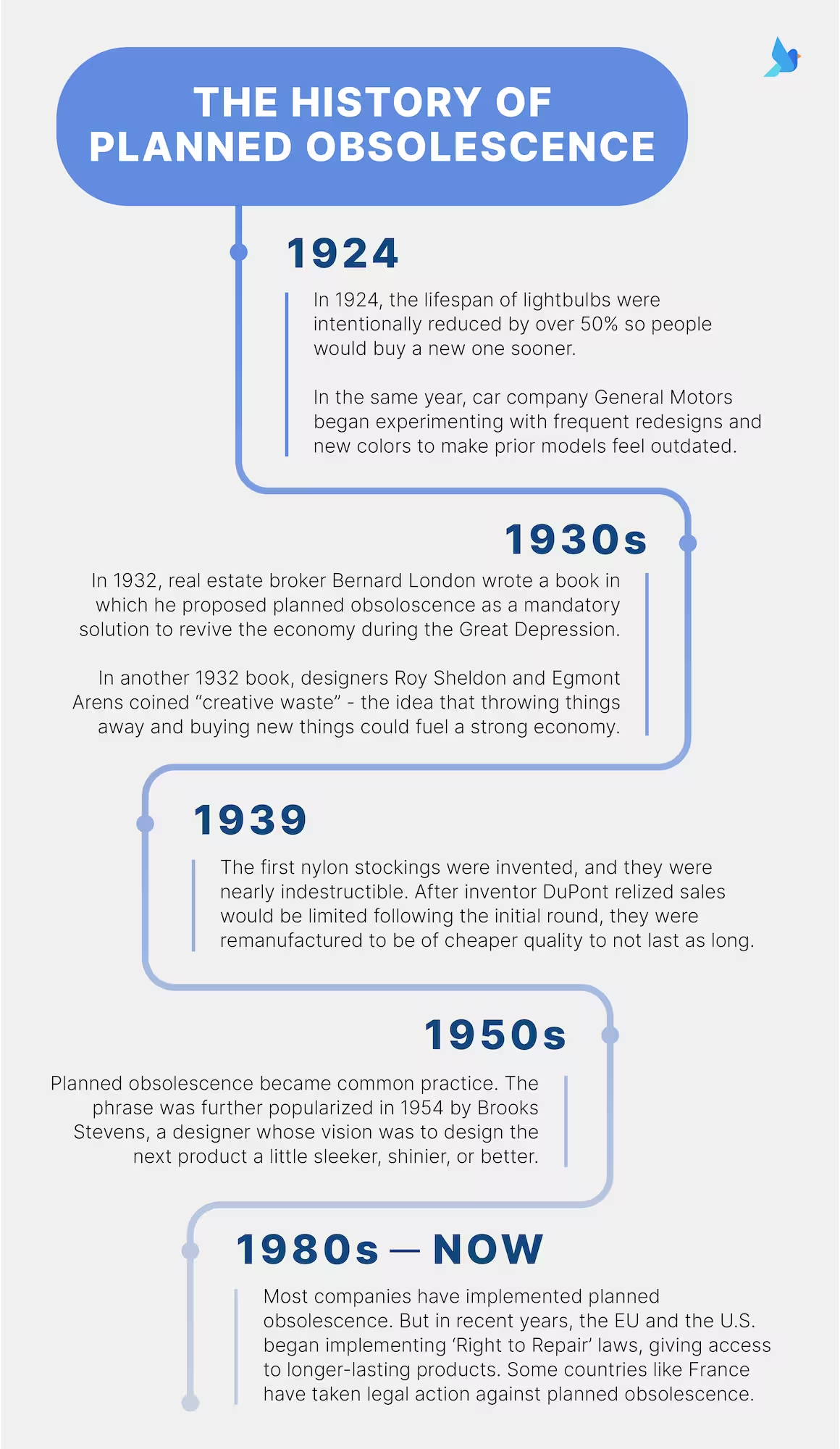

1924: It All Began With a Lightbulb

Even over 100 years ago, businesses believed that in order to be successful, they needed to sell more. In 1895, lightbulbs lasted 1,500 hours. By 1924, technological advancements improved the lifespan of the lightbulb to 2,500 hours. Lightbulb manufacturers then realized they had a problem because their lightbulbs “lasted too long”, so they formed the Phoebus Cartel which intentionally reduced the lifespan of lightbulbs by over 50%. The duration of lightbulbs was reduced to 1,000 hours so people would buy a bulb sooner. Meanwhile, prices rose.

The Phoebus Cartel was founded in Geneva by the world’s leading lightbulb companies including Philips, Osram, and General Electric.

If companies didn’t meet these requirements and a bulb was tested to last longer than 2,000 hours, they received heavy fines from the cartel. The lightbulbs were sold to the public as having “improved efficiency and brightness”. The cartel broke apart during World War II but their work lived on. The lifespan of lightbulbs continued to be limited by design for decades.

1924: Our Desire for New Things

In 1908, one of the first mass-produced cars was released – the Model T – and sold as a car that would never become obsolete. Ford said, “We want the man who buys one of our cars never to have to buy another”. There was even a toolkit that came with each Model T that allowed buyers to fix their own vehicles.

But by the 1920s, most people owned a car and no one needed a new one. Both Ford and its competitor General Motors took a hit. The CEO of General Motors was more profit-driven, so in 1924, he began experimenting with frequent redesigns and different colors to make prior models feel outdated.

Before this moment, all Ford cars were black. Each year, new colors and design features were released. This was named ‘dynamic obsolescence’ – and it worked. In 1934, the average length of car ownership was 5 years. By 1955, it was reduced to 2 years.

1932: The Term ‘Planned Obsolescence’ Was Coined

The term is credited to Bernard London, a real estate broker who wrote a book in 1932 called ‘Ending the Depression through Planned Obsolescence’. He proposed planned obsolescence as a mandatory solution to revive the economy during the Great Depression. According to London, giving all products a predetermined lifespan would provoke people to return to buy new things, and “the wheels of industry would be kept going”. In his plan to end the Depression, people would also have to pay a tax for hanging onto and using old things. At the time, this idea went pretty much unnoticed.

In another 1932 book called ‘Consumer Engineering: A New Technique for Prosperity’, authors and industrial designers Roy Sheldon and Egmont Arens termed “creative waste” – the idea that throwing things away and buying new ones could fuel a strong economy. They shared the same vision as London, arguing that society would be better off this way.

In the 1930s during the Depression, families were struggling to buy things and were saving to buy their first car or household appliances. The demand for products was reduced, but with the economic boom of the war years, the idea of planned obsolescence quickly became popular.

1939: Stockings Were Once Indestructible?!

Anyone who has worn stockings before understands the frustration of the cheap quality materials stockings are made with, typically ripping after just one or two wears. So it’s interesting to learn that in 1939, the first nylon stockings were invented to replace silk stockings and they were nearly indestructible. Everyone wanted to get their hands on them so badly that even riots broke out. But after the inventor DuPont realized that sales would be limited following the first round of sales as the stockings would last a very long time, they were remanufactured to be of cheaper quality to not last as long so people would be forced to buy more.

1950s: Planned Obsolescence Was a Normalized Concept

By this time, planned obsolescence was commonly recognized and used. The American lifestyle didn’t help as it fueled consumption. The lust for new things was already embedded into U.S. culture and people would easily be enticed.

The phrase was further popularized by Brooks Stevens, an industrial designer, graphic designer, and stylist in post-war America. In 1954, he began promoting planned obsolescence and defined it as “instilling in the buyer the desire to own something a little newer, a little better, a little sooner than necessary”. His vision was to design the next product a little sleeker, shinier, or better. Something Apple is extremely good at – and another example of what we now consider dynamic obsolescence.

1980s – Now: The Move Away From Planned Obsolescence

In the last few decades, we’ve seen various industries and large companies implement planned obsolescence. When Zara opened their flagship store in New York, The New York Times coined the term ‘fast fashion’ – the mass production of cheap clothing in response to changing trends.

Planned obsolescence became a part of school curriculums, taught in design and engineering schools as a means of promoting frequent purchases and as part of a strategy to create a successful business.

Meanwhile, a growing number of people, governments, and companies are recognizing this problem and taking action. In 2024, the EU adopted the Right to Repair directive which will be effective by July 2026. Businesses selling products covered by EU repair legislation will be forced to give incentives for repair (such as repair vouchers and funds), repair a product for a reasonable price even beyond the legal guarantee, and give access to spare parts and tools. There’s also a similar Right to Repair law in the U.S.

Some countries have also taken legal action against planned obsolescence on their own, with the best example being France – where fines of up to €300,000 and a two-year prison sentence can be imposed on companies found to be deliberately shortening product lifespans.

And many companies are taking the step towards circularity and creating higher-quality, longer-lasting products, offering repair services, or creating a platform where they can sell their products secondhand.

The Impact of Planned Obsolescence

There’s no sector that implements planned obsolescence as much as the technological sector, more specifically smartphones. Electronic waste is the fastest-growing waste stream in the world, with less than a quarter (22%) of 2022’s e-waste mass documented as being collected and recycled in an environmentally sound manner (UN, 2024).

Most e-waste ends up in developing countries piled up in landfills, unrepairable and unrecyclable. The production and disposal of e-waste are harmful to both our environment and human health, as they contain toxic chemicals including metals like lead and mercury.

So, not only does this ‘business strategy’ contribute to tons of waste, cost people tens of thousands of euros, and risk health issues for anyone involved in the production and disposal of tech products, but it also perpetuates the climate crisis.

This is nothing new (planned obsolescence), and most people know (or have an inklking) this but the article does provide solid background foundation for what we “knew”. People have joked about it for years. I’m retired, but in the 1960’s even, I remember my dad, who repaired TV’s and appliances for Montgomery Ward joking about how the older models lasted longer. My current tablet is getting dated, but works; however, where the charger plugs into the port, the connection is iffy; the repair shot said it’s a common problem but I would be better off to just replace the tablet than try to repair it. Remember, I said I was retired, so that expense is not an option….deliberate planned malfunction? Probably.

The word ‘depreciation’ is not mentioned in the article. Planned Obsolescence amounts to Planned Depreciation. Economists do not talk about the Net Domestic Product. They subtract the depreciation of Capital Goods from GDP but not the Depreciation of Durable Consumer Goods even though they added the so-called Durable Consumer Goods to GDP.

Our brilliant economists have been running the planet on defective Algebra since Sputnik.