The terms “net zero” and “carbon neutral” are often heard in heated discussions about climate change. Yet, they’re not as interchangeable as they might seem. In the post ahead, we’ll rummage deeper into the differences between net zero and carbon neutral, their idiosyncrasies, and some of the controversies surrounding carbon neutrality. How impactful are these approaches at balancing emissions out, really?

Defining net zero

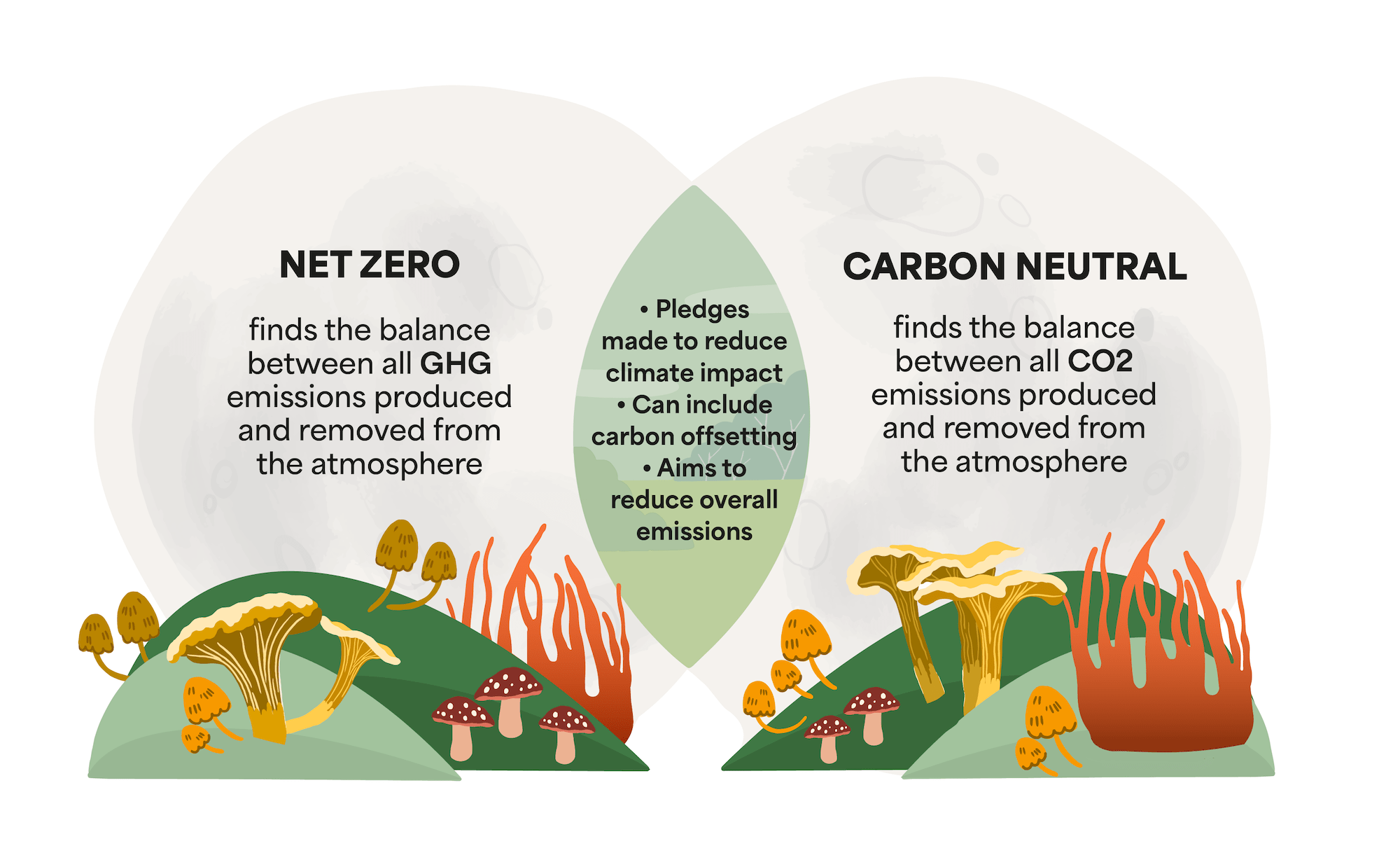

Net zero is a long-term target to find the balance between the amount of greenhouse gas emissions produced and the amount removed from the atmosphere. Achieving net zero means that emissions are counterbalanced by removals, often through tactics like carbon offsetting, renewable energy adoption, and pioneering green technologies. The goal of net zero is to ensure that the net effect on the climate is neutral.

The lower emissions are in the first place, the better – as that makes reducing them to ‘zero’ more feasible. That’s why net zero is focused on reducing emissions as well as counterbalancing.

Key characteristics of net zero:

- Not just carbon: Net zero typically encompasses all greenhouse gases (GHGs), including carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), and others. It’s an important detail because some other GHGs are much more potent than carbon dioxide, like methane which is said to have up to 80x the heating power of CO2.

- Comprehensive scope: The extent of most net zero targets includes global scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions. Carbon neutrality, on the other hand, only requires scopes 1 and 2, with scope 3 emissions encouraged and sometimes included – but not mandatory.

- Reduction focused: Emissions should be reduced as much as possible before considering offsets. The emphasis with carbon neutrality tends to be about offsetting, regardless of the baseline emissions, which is more short sighted.

- Long-term commitment: Achieving net zero often implicates long-term strategies and investments in sustainable technologies, as well as behavioral change. This is why so many countries (as well as companies) have pledged to become net zero by a certain date and that’s far into the future. The EU’s ambition is net zero by 2050. Finland has the world’s most ambitious net zero target, aiming to reach the milestone by 2035.

The problems with net zero

While the long-term commitment of net zero is pragmatic, the approach comes with serious caveats. The targets are typically so far into the distance that it’s hard to really track them and they tend to be revisited and revised. Net zero by 2050! The sincerity appears shaky when so many countries are already failing to meet the obligations of long-term legally binding agreements like the Paris Agreement, which aims at 2030.

In 2024 it was reported that New Zealand may miss its 2050 net zero commitments because of changes to government and backtracking on climate policy. At a corporate level, in early 2025, BP watered down its net zero plan – increasing its investment in oil and gas to $10bn a year and basically abandoning its targets to reach net zero set five years earlier.

It’s the time to fast-track not backtrack, so this pattern is worrying. Yet, when the destination is so distant it gives the opportunity to reroute.

Now onto the shorter-term patch. The counterpoint to net zero’s epic mission.

Defining carbon neutral

Carbon neutral is used to describe long-term ambitions pledges, like net zero. In fact, is often used – imprecisely – to describe net zero targets. But it’s also a shorter-term corporate label that typically refers to a simpler act of proactively balancing carbon dioxide emissions – in the worst cases with cheap offsets. This can be achieved through the classic tactic of planting trees, investing in renewable energy projects, manufacturing innovations, carbon capture subscriptions, or purchasing carbon credits. Unlike net zero, carbon neutrality is often criticized for focusing more on offsets rather than meaningful emission reductions.

This is why massive global companies have been known to claim carbon neutrality for their mass-produced and globally successful products. Another well-known criticism is when airlines claim to be carbon neutral by relying on offsets. It’s a trend that has even resulted in successful action for greenwashing.

Key characteristics of carbon neutral:

- Carbon-centric: Focuses on CO2 emissions, not all GHGs.

- Offset reliant: Has been dependent on carbon offset projects to neutralize emissions.

- Short-term achievability: Can be achieved more quickly than net zero, through less rigorous means.

- Limited scope: Carbon neutrality normally only looks at scopes 1-2 mandatorily.

The problems with carbon neutrality

While short-term carbon neutrality is popular, it faces skepticism and the detractors are rising. Critics argue that carbon neutrality can be spurious, offering companies a way to appear environmentally responsible without making meaningful changes to their ways. In other words, greenwashing. Or even more plainly, lies.

Here’s a quick peek at some of the main points of contention:

- The effectiveness of projects can vary, and heaps of studies have found that carbon offsetting doesn’t represent genuine carbon reductions.

- Achieving carbon neutrality does not mandate significant emission-reducing activities. Companies can continue polluting practices after clicking a button to purchase their projects.

- As a result of the previous two points (carbon offsetting not working and a lack of emission reductions), there’s a possibility that carbon offsetting causes an increase in emissions and worsens climate change.

- Carbon offsetting credits are granted for projects that would have happened regardless. New projects created as a result of emission-causing companies are considered ‘additional’. This is not required, but it is the only way for carbon offsetting to be impactful.

The best of both worlds

While both paradigms aim to mitigate climate impact, net zero provides a more comprehensive and reduction-focused strategy across all GHGs and Scopes. Yet it takes a long time to work, so long that it risks becoming a vapid pledge – perhaps even a boast. Meanwhile, carbon neutrality, though beneficial, must be pursued with diligence and data to make sure it delivers genuine benefits. It’s a shorter-term patch but then again patches can be useful.

All considered, for genuine climate action, companies and organizations should strive to achieve something meaningful from both net zero and carbon neutral’s finest points:

- Prioritize emission reductions: Focus on reducing emissions through energy efficiency, renewable energy adoption, technological innovations, and a data-driven approach that examines scopes 1-3 (maybe even 4).

- Use high-quality offsets: When offsets are necessary, make sure they are high quality, verifiable, and have a real-world impact. Projects should always be additional – i.e., they would only have existed with a prospect for project owners to sell carbon offsets.

- Commit to transparency: Maintain transparency in reporting and verification to build trust. People and stakeholders want to see results – and this can involve images and video, as well as stats.

- Get sh*t done: Both approaches have been accused of being full of empty promises. Equally, both can be pursued by people and organisations who are committed to getting the work over the line. Dogged determination is needed to bring the best out the best of either approach.

So which is better?…

So which is better?…

In the sustainability blizzard, understanding the separations and intersections between net zero and carbon neutral is pretty handy. Yet, like a lot of things related to sustainability, it’s complicated! You can’t really say either approach is perfect and you also can’t say that neither of them has value.

By blending both approaches with a firm commitment to doing (rather than saying), we could start to make a more effective transition from a high-emissions world, to a low-emissions one. Future generations would be pretty pleased about that.

So which is better?…

So which is better?…

Leave a Reply